Stannous Chloride: A Deep Dive into Its Evolution and Role

Historical Development

Stannous chloride takes its roots in the work of alchemists and early chemists exploring the world of metals and salts. During the eighteenth century, chemists learned to use stannous chloride as a useful reducing agent, discovering that it could reliably turn certain colored salts clear and bring precious metals out of solution. This compound gained attention in the industrial revolution for its ability to clean, coat, and dye materials. Later, as industries matured, stannous chloride found use in printing, textiles, and metallurgy. The road from mysterious white crystals in a chemist’s flask to an established industrial staple reveals just how useful a single chemical can become when its properties match growing technical needs.

Product Overview

Stannous chloride, most commonly produced and purchased as a dihydrate with the chemical formula SnCl2·2H2O, appears as colorless crystalline solids that dissolve readily in water. Industry refers to it by a handful of nicknames: tin(II) chloride, tin salt, and pyrostannous chloride top the list. Chemists appreciate its strong reputation as a reducing agent and a source of tin(II) ions. Companies find value in its consistent reactivity across a range of applications, from electroplating to pharmaceuticals, showing the versatile side of quite an unassuming compound.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This salt carries a molecular weight close to 225 g/mol as a dihydrate. Left out in the open, it draws moisture from the air, caking into solid chunks. Drop a few grains into water and you’ll get a clear, acidic solution with a sour tang to the nose. Heating breaks it down to its anhydrous form, which is even more eager to dissolve. Chemically, stannous chloride hands over electrons quickly. It turns iron(III) solutions colorless and morphs gold salts into flecks of metallic gold. Its solubility drops off in alkaline conditions, driving it out of solution as basic salts or hydroxides. Acids like hydrochloric acid keep it in line, helping it resist oxidation to tin(IV) compounds.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Catalogs list stannous chloride with purity levels ranging from technical grade (about 98%) up to analytical grade (99.99%). Labels cite batch number, country of origin, moisture content, and residual iron or lead. Regulations require handling instructions printed up front, with hazard pictograms for irritant and poisonous effects. Producers test for heavy metals by atomic absorption spectroscopy and for iron with colorimetric methods. Some buyers ask for “free-flowing crystals,” which means a careful drying process, though most industrial users dissolve it immediately upon receipt. Shelf life depends on how tightly the bag is sealed, and how much exposure the product gets to air and water.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers drop pure tin metal into a beaker of concentrated hydrochloric acid, kicking up fizzing hydrogen and releasing heat. The tin slowly dissolves, forming a clear solution as stannous chloride dihydrate. Evaporation removes excess solvent, and careful cooling makes colorless crystals form out. Some routes swap out pure acid for a mixture of brine and recovered industrial tin scrap, saving costs for big operations. Recrystallization purifies the product, though leaves behind traces of iron, lead, or copper when raw tin lacks purity. Commercially, the goal is to balance high output with low impurity risk—tougher when tin prices bump up.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Stannous chloride goes into the laboratory flask when chemists need to strip away oxygen. Adding it to solutions containing gold(III) chloride brings gold out of solution in shimmering leaf form, useful in historic and modern gold assays. Textile dyers once relied on its ability to stabilize vegetable dyes on cloth, using tin(II) ions as a mordant. Electroplaters call for it in baths that deposit smooth, adherent layers of tin on steel—a job made possible by its gentle reducing power. Mixing stannous chloride with stronger acids yields volatile stannous chloride gas, showing a sharp instability on heating, breaking down above 250°C.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists use “tin(II) chloride” or “stannous chloride.” Sometimes product sheets reference it as SnCl2, pyrostannous chloride, or simply tin salt. In pharmaceuticals and diagnostics, catalogs mention “chlorure stanneux” and “chloruro de estaño,” tapping into global trade. These different names all point to the same basic compound, though the dihydrate and anhydrous forms behave a little differently in storage and solution chemistry. Rarely, some blend it into proprietary tin salts with stabilizers, sold under brand names, for better shelf life or compatibility.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety protocols require gloves, goggles, and lab coats as a bare minimum. Skin and eye contact leads to burns or irritation, especially with concentrated solutions. Inhaled dust triggers coughing and breathing trouble. Accidental splash in the eye demands immediate rinsing for at least fifteen minutes. Waste must go in labeled containers and land in a hazardous waste facility, not the regular trash or sewer. Safety Data Sheets highlight its toxicity in aquatic environments, setting strict limits on industrial wastewater discharge. Annual inspections of storage areas help spot leaks and deteriorating packaging. Training workers on spill response, containment, and emergency eyewash use goes further than just printed warnings.

Application Area

Stannous chloride serves a diverse crowd. Textile companies value its role in brightening fabric colors and affixing dyes securely to cotton and wool. Electronics firms depend on it for prepping circuit board surfaces, laying down a thin, solder-friendly tin layer. Goldsmiths employ it for refining and purifying precious metals. Analytical laboratories use its strong reducing action during qualitative analysis of metal cations, making it a routine part of high school and university chemistry experiments. In pharmaceuticals, a tightly controlled grade of stannous chloride stabilizes certain antibiotics and supports imaging in radiodiagnostics. The printing industry uses it less often now, but it still pops up in certain specialty inks and etching processes.

Research & Development

Universities and corporate R&D centers continue to experiment with tin(II) chemistry. Research focuses on developing new tin-based contrast agents for medical imaging, offering more accurate diagnostics in cardiovascular and cancer scans. Materials scientists investigate stannous chloride as a precursor for building ultra-thin films in microelectronics, aiming to shrink circuit features further than ever before. Environmental chemists test methods to recover tin from exhausted plating baths, reducing waste and stretching resources. Some teams chase ways to stabilize stannous chloride against oxidation, turning it into a safer, longer-lasting raw ingredient for more applications.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists point out that stannous chloride can harm mammals and aquatic life at moderate doses. Swallowing larger amounts triggers abdominal cramps, nausea, and kidney stress, though the acute lethal dose is higher than many other metal salts. Chronic exposure may affect liver and nervous system function, especially when workers lack proper safeguards. Bioaccumulation poses a risk in aquatic environments, so regulatory bodies like the EPA and EU set low thresholds for industrial effluent. Inhalation studies on lab animals reveal respiratory tract irritation, so proper ventilation ranks as a must. Modern research tracks stannous chloride breakdown products to spot any risk of environmental persistence. Continued vigilance helps companies align with evolving health and environmental standards.

Future Prospects

Stannous chloride holds a steady place in established industries, but its future sits in modernization and smarter chemistry. Demand likely rises in electronics manufacturing as devices shrink and tin becomes the solder metal of choice. Cleaner production and recycling techniques promise less environmental impact and stronger circular economies. Researchers see promise in pairing stannous chloride with organic ligands, building new drugs and imaging agents. Green chemistry efforts might swap harsh acids for milder, sustainable alternatives, guiding stannous chloride production toward lower emissions and leaner waste streams. Success hinges on balancing cost, safety, and environmental goals, drawing on lessons from decades of research and experience.

The Role of Stannous Chloride in Industry and Everyday Life

Stannous chloride, known in labs as tin(II) chloride, pops up across different industries and everyday situations. In my experience as a writer who has dug through research journals, chemical suppliers, and manufacturing interviews, learning where this chemical fits in pulls back the curtain on a lot of products we often take for granted.

Hidden Hand in Metal Work and Electronics

Factories that deal with metals often turn to stannous chloride as a reducing agent. It takes metal ions and helps turn them into their metallic form. That matters a lot in making tinplate, which lines cans and helps prevent rust. This coating process protects what goes inside—anything from beans and soup to paint thinner. Without this chemical step, shelf lives drop quickly and food waste climbs.

Shifting over to electronics, stannous chloride acts as a bridge when plating circuits or building semiconductors. It lays down a “seed” layer so precious metals like gold can attach smoothly to circuit boards. Growing up, I tinkered with electronics, always amazed at how a tiny shiny spot could mean the difference between a gadget working or breaking down. Harsh shortcuts in manufacturing, with lower-quality chemistry, send failure rates through the roof. So, chemicals like stannous chloride keep quality control in check.

Impact on Medicine and Lab Tests

Stannous chloride also shows up in healthcare. Hospitals run diagnostic imaging tests, and technetium-99m scans use compounds prepared with stannous chloride. This helps doctors see bones and organs more clearly—crucial for catching problems before they spiral. The reliability of these tests means earlier and more accurate treatments for patients.

In the research world, this chemical plays a role in detecting metals. Mix it into a test solution to spot small traces of mercury or gold. For scientists chasing solutions to industrial spills or contamination, being able to spot toxins fast can save money and health. Early detection technologies often rely on these tried-and-true reactions.

Presence in Consumer Products

Companies that sell toothpaste, especially those for people with sensitive teeth, lean on stannous fluoride, which they often make starting from stannous chloride. It’s a detail buried on ingredient lists, but it plays a big part in reducing pain from exposed nerves and blocking bacteria. Anyone who has dealt with toothache probably remembers the relief from switching to a paste that contains this ingredient.

Challenges and Safer Handling

No chemical comes without risk. Stannous chloride, like many industrial compounds, can cause skin irritation and health hazards if handled carelessly. On factory floors, safety training and oversight must become routine. Bigger companies set a better example, but small suppliers sometimes cut corners. Regulators, workplace inspectors, and management have to stay plugged in to keep everyone safe. Ease of access runs up against safety, and the line shouldn't blur.

Room for Improvement in Sustainability

Production of stannous chloride generates waste, so chemical engineers constantly look to recycle these byproducts or cut down on pollution. Progress in green chemistry finds its way into daily practice when teams share the wins, not just within companies but across industries. Incentives for recycling, using alternative compounds where possible, and strict disposal guidelines make a real difference.

People rarely think about the journey behind a can of soup or a tube of toothpaste, yet small chemicals pave the way for these comforts. Greater transparency, smarter oversight, and a culture of sustainability will shape how stannous chloride fits into the world of tomorrow.

A Closer Look at Safety in Everyday Chemicals

People often wonder about the chemicals used in daily products, especially stannous chloride. I remember working in a small laboratory where stannous chloride played a role in tests for gold and used for glass coloring. Right from opening the bottle, I recall the sharp, pungent odor that meant gloves and goggles should stay on—no shortcuts. This chemical demands respect, but the story doesn’t stop with a whiff in the lab. It goes further into health, environmental concerns, and workplace exposure.

Health Risks: Not Just a Lab Issue

Stannous chloride, also called tin(II) chloride, starts as a white crystalline powder. Moisture in the air makes it damp pretty quickly. Now, if a person inhales dust or fumes, eyes may sting and lungs may start to burn. My own colleagues have felt irritation—nothing subtle—after accidental exposure. Skin contact brings rashes or blisters in sensitive folks. Swallowing it on accident could mean nausea and stomach pain. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lays out these dangers pretty clearly, backing up what many of us have seen firsthand.

Folks with allergies, asthma, or sensitive skin can land in real trouble after even short encounters. I keep thinking about this every time I see janitors and maintenance workers restocking supplies in schools or hospitals, passing by chemicals they barely recognize on the shelf.

Environmental Impact: Beyond the Workspace

Stannous chloride isn’t just a hazard indoors. If poured down the drain or tossed with regular trash, it can find its way to waterways. There it can poison fish and tiny aquatic life. Even plants at the edge of streams feel the hit after repeated contamination. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set standards for disposal, but gaps in training cause mistakes, and run-off happens.

On a personal note, I’ve seen waste buckets labeled “hazardous” end up with regular garbage bags simply because busy workers didn’t get enough training. All it takes is one rushed day to let dangerous material slip into the wrong bin. Those moments lift the risks beyond the people who use the chemical—extending trouble to whole communities.

Safer Practices: What Works in Real Life

Knowledge stands as the strongest defense against harm. Employers who train their teams regularly have far fewer accidents. I once took a class on chemical safety that used real scenarios, not just binder notes. We practiced using spills kits, cleaning up broken bottles with absorbent pellets, and rushing to eyewash stations with our eyes shut. Those drills brought the lessons home in ways a checklist never did.

Labels demand attention. Everyday labels featuring signal words like “Danger” or “Warning” actually do cut down on risky behavior. Wearing gloves, goggles, and masks—the old rule of thumb that seems obvious—saves more eyes and lungs than any slick packaging claim. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) sets guidance here, but leadership drives day-to-day practice.

On a community level, better disposal options stand out as a real solution. Battery and chemical take-back days, plus visible disposal sites in neighborhoods, keep these chemicals out of the wrong streams and trash piles. Urban and rural areas both gain by making safe disposal routine, not an afterthought.

A Practical Approach Matters Most

Stannous chloride causes harm if handled wrong. Few chemicals used by artisans, labs, or industry workers carry zero risk. Treating them with clear protocols, honest education, and working disposal plans works better than pretending the risk isn’t there. Looking after both the people using it and the places where waste might end up gets results. Every label, safety drill, and local take-back event makes a real difference.

Understanding Stannous Chloride’s Nature

Stannous chloride, or tin(II) chloride, often appears as a white crystalline solid that turns yellow on exposure to air. This change signals trouble since exposure leads to oxidation and reduces its usefulness in the lab or industry. Moisture and air don’t work in its favor, wrecking purity and causing it to clump or dissolve, so storage solutions aim to protect it from these elements.

Real-World Storage Concerns

I once worked in a teaching lab with glass jars full of basic chemicals, stannous chloride among them. After a couple of months in a poorly sealed jar, it didn’t look like the sample we had started with. The cloudiness warned us that air and moisture had changed its character. In scientific and industrial work, relying on degraded chemicals wastes time and money. Damaged stannous chloride can also mean inaccurate measurements or ruined products in manufacturing, so keeping it sound matters to anyone serious about results.

Keeping Air and Water Out

All good storage begins with the right container. Glass with a tight seal stands out, although some use heavy-duty plastics. Wide-mouth jars sometimes invite in too much air during scooping, so narrow jars limit this risk. For something especially vulnerable like stannous chloride, it helps to work quickly, open containers only when necessary, and get the lid back on right away. Some labs use a dry box or desiccator—simple tools packed with drying agents—to keep the air inside bone-dry. Silica gel packets work for home setups; labs often reach for more advanced desiccants.

Light and Temperature Matter

Sunshine speeds up chemical breakdown. Even indirect light can shift a substance’s composition bit by bit. So, it makes sense to keep tins of stannous chloride tucked away in cabinets or boxes, far from windows and other bright spots. Room temperature usually works, but if a place heats up over the course of a day (think of a warehouse or prep room), storage space should stay cool and stable. Heat increases reactivity, so cooler storage brings an extra layer of safety and longevity.

Labeling, Safety, and Oversight

Old, unmarked jars and mystery samples cause safety headaches. Splits between batches or leftover powders collecting at the back of shelves sometimes create real risk. Clear labels with purchase dates, batch information, and hazard warnings keep everyone on the same page. Safety sheets (SDS) near the storage spot take away the guesswork during emergencies. Eye protection and gloves become second nature after years in labs, and they stop accidents before they start—stannous chloride shouldn’t come into contact with skin or eyes, as it can irritate both.

Smart Handling Reduces Waste

Instead of buying giant containers that last years, smaller portions cut down on waste. That keeps things fresher by the time they’re used up. Keeping stock rotates the oldest batch to the front, so it never lingers too long. Institutions with chemical management systems tie all these pieces together—tracking inventory, monitoring use-by dates, and ensuring old samples get disposed of safely, never dumped carelessly.

Looking Ahead

Careful storage of stannous chloride protects health, budgets, and the integrity of lab and factory work. Wrapping knowledge, common sense, and basic discipline around this powder shows it’s about more than following rules—it’s about valuing what could go right and preventing what might go wrong.

Why SnCl2 Matters Outside the Chemistry Lab

Stannous chloride, or SnCl2, shows up well beyond the periodic table. Plenty of us use toothpaste with stannous fluoride—a close cousin—to fight gum disease and sensitivity. Behind that, factories lean on SnCl2 to make dyes, mirror coatings, and even add color to ceramics. For a chemical most folks never hear about, it’s quietly woven into countless products.

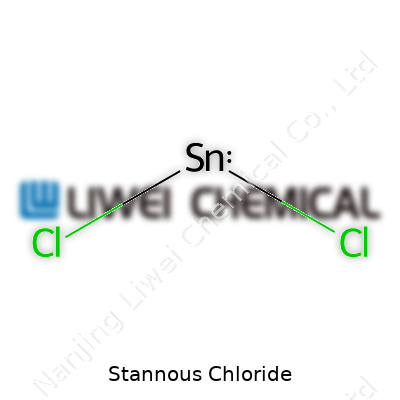

The Structure Behind the Formula

Stannous chloride comes from tin in the +2 oxidation state paired with two chloride ions. Once I learned tin sits lower on the periodic table, the strange behavior of this compound made more sense; in water, white crystals dissolve only with careful handling. That reactivity makes it a favorite for textile printing and electrolytic baths, since SnCl2 interacts without much fuss yet gives back reliable results.

Everyday Risks and Smart Handling

Chemicals like SnCl2 work wonders for industrial production but don’t belong around kids or pets. A drop can cause skin burns or eye irritation. Breathing in the powder leads to coughing and mild respiratory trouble. From personal experience running a high school chemistry demo, I saw how important goggles and gloves really are. It’s tempting to think substances from the science lab are harmless in tiny amounts, but short-term care matters as much as long-term cleanup.

Environmental Impact and Responsibility

Factories and labs generate waste streams that sometimes put stannous chloride in local waterways. Studies from environmental agencies found that excess tin salts alter pH balances downstream. I’ve seen community groups spring into action when river samples spike with heavy metals. Filters and neutralizing chemicals help in treatment—these are solutions that tech teams developed by going case by case, finding local fixes instead of one-size-fits-all answers.

Quality Control and Trust

Most users outside manufacturing think about clean water or safe products, not molecular formulas. Companies selling ingredients like SnCl2 bear the responsibility, so regular purity checks aren’t just red tape—they guarantee safety. Once, I watched a supplier’s shipment get held because the tin content ran too high. Even a small error could have ruined a paint run or tainted a consumer good.

Better Alternatives and Sustainable Choices

Some industries began swapping out stannous chloride for less reactive compounds to reduce hazardous leftovers. Solar panel factories, for instance, investigate substitutes that keep efficiency up but health risks low. That shift doesn't mean SnCl2 vanishes overnight; instead, research leads people to rethink where it brings the most benefit with minimum downside.

Keeping Safety Front and Center

Schools could play a bigger part by teaching the real-world side of chemicals like stannous chloride—not just the periodic table facts, but the smart habits for storage, disposal, and emergency response. That keeps younger generations aware and better prepared, pushing for stronger standards where people, environment, and industry connect.

Turning to Science for Safer Water

Plenty of folks get uneasy about what comes out of the tap, and for good reason. Clean, safe water supports health and daily life. Water treatment plants lean on chemicals to make sure our water stays clear of heavy metals, algae, and all sorts of unseen troublemakers. Stannous chloride—also known as tin(II) chloride—gets some attention as a possible player in this line-up. Its reputation in chemistry circles runs deep, but using it for what we drink and bathe in deserves a close look.

The Chemicals Doing the Heavy Lifting

Water runs through miles of pipes, picking up all kinds of particles and dissolved stuff along the way. Classic water treatment outfits often use aluminum or iron salts in a process called coagulation. These help clump dirt, bacteria, and other grime into larger particles, which get filtered out more easily. People ask if stannous chloride can fill a similar role or maybe do something those other chemicals can't.

In lab work, stannous chloride is a strong reducing agent. That quality makes it attractive—especially for handling things like chromium(VI), a dangerous form of chromium linked to cancer. The EPA flags chromium(VI) as a big concern in drinking water. With its knack for reducing this metal to the far safer chromium(III) form, stannous chloride has value that extends beyond the textbook. Places dealing with groundwater polluted by industry can’t always count on standard approaches. Adding stannous chloride to the process sometimes gives a practical shot at making water safer.

Weighing the Benefits and Risks

Still, stannous chloride brings more than just positive results. It carries tin into the water, and tin has its own health risks, especially if it builds up. The WHO sets strict limits for tin in drinking water—2 mg per liter—so it doesn’t take much to cross the line. There’s also worry about what by-products might show up when stannous chloride meets other chemicals, especially chlorine. Some of these by-products turn out to be more stubborn or even toxic.

In my own work testing out different water treatment chemicals for small communities, the choice always comes down to a balance. What solves one problem sometimes creates another. Before turning to chemicals like stannous chloride, plant operators want solid data on side effects, waste disposal, and constant tin monitoring. Tweaking doses might work in a controlled lab, but on a citywide scale, the stakes jump up fast.

Practical Solutions and Looking Ahead

Running a water treatment operation well calls for a look at the whole picture. If hexavalent chromium levels present a clear threat and all the usual methods fall short, stannous chloride deserves a spot in the toolkit—as long as operators track tin content and test for by-products at every step. Enforcing these checks costs money and expertise, but they form the base of safe water delivery.

Better investment in research always pays off. Funding more field studies would answer how tin holds up in different water sources and climates. Equipping plant workers with modern testing tools goes hand in hand with safer water. From my own experience, communities that keep science close and pay attention to the details usually end up with better water and fewer surprises down the road.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Dichloridostannane |

| Other names |

Tin(II) chloride

Tin dichloride E512 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈstæn.uːs ˈklɔː.raɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7772-99-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1206953 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:78029 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1200972 |

| ChemSpider | 20525 |

| DrugBank | DB09144 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.175 |

| EC Number | 231-868-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 77852 |

| KEGG | C13587 |

| MeSH | D013243 |

| PubChem CID | 24015 |

| RTECS number | XO6475000 |

| UNII | 232BXD1QZ4 |

| UN number | UN3260 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8020227 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | SnCl2 |

| Molar mass | 189.62 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.71 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -4.1 |

| Vapor pressure | 1 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.32 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -51.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.806 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.77 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 129.0 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -320.4 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V03AN02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Toxic if swallowed. Causes skin irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302, H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P312, P330, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P302+P352, P332+P313, P362+P364, P304+P340, P312, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ Oral Rat: 700 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 700 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SS4300000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) of Stannous Chloride: "2 mg/m³ (as tin, OSHA TWA) |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 100 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Stannic chloride

Tin(II) sulfate Tin(II) oxide Tin(IV) oxide |