Sodium Carbonate Decahydrate: Roots, Realities, and Research

Historical Development

Chemists first came across sodium carbonate decahydrate centuries ago during the search for better glass-making substances. In ancient Egypt, people used naturally occurring natron, which held mixtures of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate. By the 18th century, the Leblanc process let humans produce soda ash on purpose, forever changing industries that thrived on glass, textiles, and soap. The true leap forward came through the Solvay process, introducing cost-friendly, industrial-scale sodium carbonate while water crystallization gave rise to the decahydrate form. Each development shaped how factories cleaned, dyed, cured, and preserved goods, and it’s no overstatement to say the chemical’s evolution has rippled across technology as much as everyday life.

Product Overview

Sodium carbonate decahydrate—often called washing soda—looks like chunky white crystals or powder. Its composition includes sodium carbonate with ten molecules of water. Folks find it in the lab, tucked in laundry rooms, and inside chemical plants. The decahydrate dissolves in water fast, raising the liquid’s alkalinity in ways that tackle hard water, clean surfaces, and shift chemical balances. It doesn’t just clean, though; it keeps industrial pipes clear, boosts textile dyes, and acts as a buffer. It shows up in routine cleaning, in glass works, and behind the scenes in a bunch of surprising places.

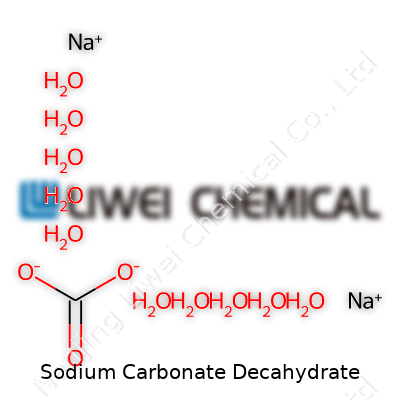

Physical and Chemical Properties

Sodium carbonate decahydrate forms glassy granules or chunky white monolithic crystals. The compound’s molecular formula clocks in at Na2CO3.10H2O, and it tips the scale at a relative molecular mass of about 286. The crystals melt and lose water at moderate temperatures, drying out to pure sodium carbonate above 34°C. Toss it in water and it dissolves fast, cooling the surroundings as the water of crystallization pulls heat; this solubility makes it versatile in laundry and cleaning. Touch the solid crystals, they feel slippery—thanks to their alkaline pH, close to 11. The material reacts fine with acids, fizzing as carbon dioxide bubbles escape and new salts get made. Stored under normal indoor conditions, the decahydrate doesn’t mind unless humidity or heat gets high enough to pull off the water of crystallization.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Industry standards demand purity levels topping 99% for technical-grade sodium carbonate decahydrate. Labels on sacks or drums mark net weight, batch numbers, manufacturer codes, and hazard statements—since eye or skin exposure causes irritation. Manufacturers must follow chemical hazard labeling rules, using GHS pictograms and safety warnings. Bags come moisture-sealed or lined, since the crystals soak up water and degrade in damp. Trade paperwork calls out the proper shipping name, UN classification (often UN 3077 for environmental hazard), and recommended handling instructions. Details like grain size, free-flowing quality, and the absence of abrasive grit set some grades apart, especially where high-end cleaning and precise dosing matter.

Preparation Method

Modern production lines pump out sodium carbonate decahydrate using the Solvay process. Brine gets treated with ammonia and carbon dioxide to form sodium bicarbonate. After precipitation and filtering, warming converts bicarbonate to carbonate. Workers take pure sodium carbonate, dissolve it in cold water, and cool the solution just right, coaxing the decahydrate crystals to form and drop out. Skilled staff rake, wash, and dry these crystals fast, since warm air strips out the bound water and ruins the decahydrate. Across plants worldwide, the process balances energy use, resource costs, and strict environmental controls to make high-purity washing soda at scale.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

In chemistry labs, sodium carbonate decahydrate makes a splash as a base, leaping into double displacement reactions. Added to acid, it yields salt, water, and plenty of carbon dioxide gas. Heating the decahydrate above 34°C drives off water molecules, shrinking crystals down to anhydrous sodium carbonate, which brings other uses in glass-making and metallurgy. Reacting it with calcium hydroxide produces caustic soda, which happens on the industrial scale in many countries. Mixing sodium carbonate with various dyes or surfactants leads to specialty blends for laundry work. The base form helps neutralize acids, stops corrosion, and supports even new-age processes like water softening in municipal treatment plants.

Synonyms and Product Names

Different industries and books give sodium carbonate decahydrate a mix of names: washing soda, soda crystals, sal soda, and hydrated soda ash crop up often. Commercial packaging uses trade names tied to certain suppliers, but on chemical lists and safety records, the names above signal the same substance. Scientific circles often cite its CAS number, 6132-02-1, which narrows down the decahydrate form apart from plain anhydrous sodium carbonate or the monohydrate version.

Safety and Operational Standards

Operators working with sodium carbonate decahydrate wear goggles and gloves, since the dust stings eyes and dries out skin. Inhalation over long stretches causes sore throat or coughing fits, so masks or dust collectors matter in bulk-handling plants. If spilled, workers sweep up dry crystals, rinse off any surfaces, and flush residues down drains with plenty of water. Fire risk from sodium carbonate decahydrate runs low, but it reacts with acids, so every plant keeps acids and bases apart. Emergency kit shelves carry neutralizing agents and clean water. Storage calls for dry, cool spaces, in sealed containers that block moisture and drafts. Manufacturers post safety data sheets, outlining every risk and remedy based on learned practice and regulatory rules under OSHA and local law.

Application Area

Laundry rooms, glass factories, chemical plants, and water treatment stations lean on sodium carbonate decahydrate whenever boosting alkalinity matters. Cleaning powders bank on its ability to pull grease and mineral stains from fabric. In textile dye houses, it locks in bright colors by prepping fibers. Glassmakers melt it with silica and lime to lower furnace temperature, saving energy. Water treatment operators dose it to soften municipal water, getting rid of scale and extending city pipe life. Swimming pool techs rely on it to bump up pH, keeping pools safe and clear. Even in the arts—pottery, ceramics, dye craft—artisans use washing soda for scouring clay and prepping dyes. Every one of these industries depends on a steady, affordable source, and a supply chain that keeps standards high.

Research and Development

Academics and industry researchers seek smarter ways to produce, use, and recycle sodium carbonate decahydrate. Studies zero in on energy savings in crystallization and recovery, often marrying classical physics with machine learning to cut waste. Environmental teams develop methods for recycling wash waters loaded with sodium and carbonate ions, closing the loop for eco-friendlier operations. In analytical chemistry, researchers measure trace heavy metals by exploiting sodium carbonate’s base properties. Recent patents focus on forming specialty blends for green detergents or using sodium carbonate as a CO2 sorbent—two uses that build on classic applications with a sustainability twist. New testing explores slow-release forms for industrial cleaning, targeting sectors where water conservation matters.

Toxicity Research

Traditional safety data lists sodium carbonate decahydrate as only mildly hazardous, but longer-term occupational studies dig deeper. High doses by mouth irritate the stomach and intestines, so labeling stresses its nonfood character. Animal trials show large amounts disrupt electrolyte balance and cause mild toxic symptoms, but toxicity sits lower than many other cleaning or manufacturing agents. Skin contact dries and cracks hands, but allergic reactions barely register. Recent medical reviews look at cumulative exposure in laundries, city water plants, and glass factories—linking dust control and ventilation with fewer cases of chronic irritation. Results so far point to sensible protective gear, regular training, and clear safety signage as the most reliable defenses.

Future Prospects

Shifting rules about water pollution and energy costs force chemical makers to rethink soda ash and its hydrates. Sodium carbonate decahydrate sits strong in traditional sectors, but researchers push to use it as a carbon-capture agent and as a key in greener cleaning products. Factories invest in automated crystallization, precision dosing, and closed-loop washing to shape cleaner supply chains. Urban planners eye it for broader water softening and critical minerals recovery. As recycling tech matures, more cities may reclaim and reuse spent sodium carbonate, shrinking chemical footprints and slashing costs. In labs, new crystal forms and composite blends pop up—each promising a new take on an old, reliable material. That mix of history, practicality, and innovation keeps sodium carbonate decahydrate woven into industrial progress for years to come.

More Than Just Washing Soda

Sodium carbonate decahydrate, known by many as washing soda, brings plenty of practical uses to the table. I’ve always found that understanding where and why a compound gets into everyday life helps put its value into perspective. Over the years, people have used it most for cleaning, water treatment, and glassmaking. Sitting in my own garage, a box of it rests on a shelf next to the laundry soap—ready for the next round of tough stains.

Household and Industrial Cleaning

Dirt and grease don’t stand a chance against sodium carbonate decahydrate. With its alkaline nature, it tackles stubborn marks and residues in laundry and on kitchen counters. My grandmother swore by it for brightening dull whites. She’d dissolve a scoop in warm water, soak grimy towels overnight, and always said the results spoke for themselves. Companies like ARM & HAMMER have relied on this mineral for years to power their cleaning products. Its ability to break down organic stains has improved both home and commercial cleaning routines.

Water Softening Works

Hard water causes headaches across the country—scaly kettles, sluggish washing machines, and spotty dishes. Sodium carbonate decahydrate comes into play here, removing calcium and magnesium ions from water. These minerals cause limescale, which gunks up appliances and plumbing. By using sodium carbonate in water softeners, the flow stays smooth, clothes rinse out cleaner, and coffee pots keep running longer. Many municipalities rely on sodium carbonate for big-scale water treatment. This one compound saves folks a bundle over time by reducing equipment breakdowns and lowering the cost of cleaning supplies.

The Science of Glassmaking

Modern glass wouldn't look the same without a dash of sodium carbonate decahydrate. Glassmakers use it to lower the melting point of silica, making production safer and more energy-efficient. Without sodium carbonate, factories would burn a whole lot more fuel, which hits the environment and the wallet hard. The float glass used in car windows, building facades, and smartphone screens often gets its shine thanks to a carefully measured batch of this compound. Glass remains an essential material, and sodium carbonate continues to play a huge role in keeping it affordable and available.

A Boost in Other Industries

Some folks forget how deeply sodium carbonate reaches into food and medicine. Bakeries use food-grade sodium carbonate to regulate acidity, especially in pretzels and ramen noodles, creating the familiar chewy texture and golden color. The pharmaceutical field applies it to balance pH in certain medicines and to help purify chemicals during production. Even swimming pool owners regularly drop a scoop of sodium carbonate decahydrate into the deep end. It helps balance pH and keeps water clear, fending off algae and eyes that sting every summer.

Safety, Storage, and Smarter Use

It’s important to respect sodium carbonate decahydrate’s strength. While it fights dirt on floors and glass in windows, skin and eyes need a little protection if handling it straight. Gloves and goggles do the trick. At home, I always keep the box sealed and away from food and little explorers. With growing concern around chemical waste, some manufacturers search for ways to reclaim and recycle sodium carbonate from water treatment and industry leftovers. This keeps it moving through a closed loop, working harder for longer and having less impact on our rivers and fields. Solutions like this keep the old favorite relevant as both society and science evolve.

Understanding What You’re Dealing With

Sodium carbonate decahydrate, often called washing soda, feels familiar in laundry rooms and science classrooms. It looks like a pile of frosty crystals, but don’t let the harmless appearance fool you. Years of cleaning and experiment work have taught me that even household chemicals deserve some respect. Unpacking what safety means for sodium carbonate decahydrate means looking at both personal experience and proven science.

The Science and Potential Hazards

The science is clear: sodium carbonate decahydrate mostly poses a low risk compared to strong acids or bases. Still, it’s an alkaline salt, so it can irritate your skin, eyes, or respiratory system. Rubbing your eyes after touching these crystals usually leads to redness and stinging. Even inhaling the dust can trigger coughing or a sore throat.

Occupational health data backs up these facts. The CDC’s NIOSH database includes sodium carbonate along with a long list of industrial chemicals, as workers in glass making, detergent production, and water treatment all use this substance. The takeaway from multiple case studies is straightforward: treat it like a basic irritant, not a harmless powder.

Personal Encounters in Home and Lab

I learned early on to avoid handling any powder with bare hands, even those marketed as “green” or “natural.” Once at home, I spilled sodium carbonate decahydrate near the sink. Thinking nothing of it, I swept it up barehanded. Afterward, I noticed my fingers felt dry and itchy. A friend of mine in water treatment had a similar outcome after working with it all day—raw knuckles and chapped skin.

In science labs, supervisors drive home the need for goggles and gloves even for mild chemicals. If the powder flies up, it hurts to get it in your eyes, and rinsing out stinging eyes is never fun. Cases of chemical conjunctivitis—eye irritation from contact—have been documented in teaching labs because somebody snatched the safety glasses off too quickly.

Advice from Real-World Use

At home, people often use sodium carbonate decahydrate for stubborn cleaning jobs or to boost laundry. The tendency is to treat it like baking soda. Based on my own mishaps and industry sources, the smart move involves using gloves, especially for big jobs or prolonged contact. Protective eyewear comes in handy for pouring out quantities that might puff dust into your face. Keeping good ventilation helps with any possible dust.

If you do get it on your skin, rinsing off with water always helps. Eyes need immediate flushing with water for several minutes. Poison control centers also remind users that swallowing large amounts causes stomach upset and vomiting. Like many folks, I usually keep chemical packages well out of the way of children and pets. Too many accidents start with leaving containers under the sink, where someone looking for a snack might accidentally get into something dangerous.

Getting Safety Right

For chemical professionals, the consensus still leans toward practicing good personal hygiene—wash up after handling sodium carbonate decahydrate, avoid inhaling powder, keep safety data sheets accessible, and never eat or drink near chemicals. Consistent, simple steps beat cleaning up after a preventable accident. From firsthand mistakes and industry standards, you only need a little caution to avoid real trouble with this common salt.

Understanding the Basics

Sodium carbonate decahydrate shows up as a humble pile of crystalline powder, yet its place in daily life reaches beyond the classroom or the back corner of a supply cabinet. Its chemical formula, Na2CO3·10H2O, spells out the full story—two sodium atoms, one carbonate group, and ten tightly held water molecules. In school, folks often breeze past the “decahydrate” part, not realizing those water molecules change behavior and use.

Where Chemistry Meets Real Life

Few people outside certain trades grab a bag of sodium carbonate decahydrate on purpose. Still, countless households rely on its stubborn ability to soften water and remove stains. Growing up in a region with hard water, I’ve watched a simple scoop of “washing soda”—a common name for this chemical—clear cloudiness on glasses and boost the muscle of laundry detergent. Ten water molecules make these crystals larger, easier to handle, and safer to work with compared to pure sodium carbonate, which can irritate skin and eyes more quickly.

How This Compound Stacks Up in Industry

Stepping into factories, the decahydrate form gets used to balance pH, help break down stubborn greases, and keep boilers running without scale build-up. Those water molecules keep the product flowing, stop it from clumping up, and lower the risks linked with dust inhalation. Many cleaning products owe their reliability to this exact chemical blend, and anyone relying on energy-efficient dishwashers or industrial cleaning knows the edge it provides.

Why Knowing Formulas Matters

Getting the formula right isn’t about passing a quiz—errors echo through science, industry, and safety. Ask any lab technician who’s misread a label and ended up with a reaction running hotter than expected. The difference between anhydrous sodium carbonate and its decahydrate cousin means a difference in weight, water content, and final results. Ten molecules of water per formula unit isn’t just trivia; it shapes dosing, cost, and even storage requirements. Solutions mixed with the decahydrate come out at different concentrations, and anyone working around this chemical learns to calculate on the fly to avoid errors.

Potential Pitfalls and Finding Better Ways

Mix-ups surface almost everywhere—from janitors mixing cleaning products to students in a chemistry lab. Misunderstanding what the “decahydrate” tag means can lead to weak solutions or even skin irritation from overdosing. Safety data sheets, clear packaging, and hands-on training help, but there’s more to tackle. In my experience, educational gaps often trip up newcomers far more than the complexity of the formula itself. Teachers, supervisors, and manufacturers gain more trust and fewer accidents by sticking to precise communication, consistent labeling, and practical demonstrations instead of dry lectures.

Moving forward, technology has a role—apps and calculators that break down chemical names and formulas in plain language can turn a label into clear action. Companies leading on clear instructions and pictograms simplify life for everyone. At the end of the day, a simple compound like sodium carbonate decahydrate reminds us that chemistry isn’t just for scientists. It’s for laundry rooms, kitchens, workshops, and water pipes everywhere—shaped by a little formula and a lot of experience.

Why Storage Choices Matter

Few substances change so quickly when faced with the wrong environment as sodium carbonate decahydrate. Crack open a bag and leave it open in a damp storeroom, and soon, powder gives way to clumpy, sticky cakes. This isn’t a problem just for the sake of tidiness; the chemical’s shelf life, consistency, and the outcome of any process relying on it all take a hit.

Understanding the Material’s Soft Spots

Sodium carbonate decahydrate carries ten molecules of water with every molecule. Its structure holds onto this water under the right conditions, but warmth and humidity coax the hydrate to release it as vapor. Once those water molecules leave, the powder stiffens, lumps, or even turns into less useful anhydrous forms.

In my early days in a ceramics studio, I saw firsthand how a bulk order stored in an unventilated container by a window crumbled to dust. The lesson? The tiniest shifts in weather ruin an entire batch.

Steering Clear of Trouble: Smart Storage Practices

A dry, cool room changes everything. High humidity makes sodium carbonate decahydrate weep and clump, but air below 50% relative humidity keeps it crisp and free-flowing. Anyone who’s kept it in a damp basement has spotted the gritty mess that follows.

Good storage starts with containers. Plastic buckets with tight lids or lined metal drums shut out not just air, but accidental splashes. For labs or personal projects, wide-mouthed jars with gasket seals pay for themselves over time, especially if humidity spikes during the summer.

Nobody wants a chemical that absorbs smells or dust from another product. Separate storage runs a real benefit. The further sodium carbonate sits from solvents, acids, and anything pungent, the less likely those molecules will foul up experiments or mixes.

Labeling, Handling, and Health

Any container holding a powdered chemical benefits from a clear, large label—think chemical name, purchase date, and, if possible, the source. I’ve pulled open too many containers in workshops only to find mystery powders. Some folks downplay the risk, but confusion leads to ruined supplies or, worse, safety hazards.

Some labeling solutions use color coding or QR stickers for digital tracking. Quick access to storage and safety data not only saves time but also helps others avoid mix-ups if supplies swap hands or pass between departments.

Trouble Signs and Fixes

No matter the care, containers sometimes sweat or go missing for months behind stacked boxes. Caking gives away bad storage long before a chemical test. Sometimes, breaking up lumps with a clean, dry rod works for a small amount, but severe clumping means contamination and waste.

Some users rely on desiccant packs inside the storage container to fend off humidity. Switching out packs quarterly or whenever they feel soft goes a long way. And no amount of drying ever restores degraded sodium carbonate decahydrate to its original quality, so prevent problems from the start.

Big-Picture Impacts and Better Habits

Reliable storage for sodium carbonate decahydrate isn’t about perfectionism; it’s about keeping supply costs down and ensuring every student, technician, or tinkerer starts with powder that performs as promised. I’ve learned that a few practical decisions—seals, location, clear labeling—make all the difference. Anyone working with chemicals benefits from building these habits in right from the first delivery.

Understanding the Chemistry

Walk into any hardware store or speak to anyone in glassmaking, and you’ll come across two core forms of soda ash: sodium carbonate decahydrate and anhydrous soda ash. Both share the same root substance, but they show up in industry and daily use for very different reasons. The big difference hinges on water content. Sodium carbonate decahydrate packs in ten water molecules per formula unit. Anhydrous soda ash, like its name gears toward, skips the water altogether.

Looks, Handling, and Storage

Decahydrate soda crystals feel wet to the touch and usually show up as large, see-through crystals. Think of the time you found “washing soda” in the laundry aisle—it clumps up in the container if humidity sneaks in, and the bag gets heavy fairly fast. Anhydrous soda ash comes as a white, dry powder. This means it stays light, and factory storage racks can hold more of it for the same chemical punch. Folks working in warehouses save on transport costs because they skip hauling all the extra water in the decahydrate stuff.

Weight and Active Ingredient

What really matters in factories and water treatment plants is the amount of available sodium carbonate you get per kilogram of product. Decahydrate, weighed down by those water molecules, only delivers about 37% sodium carbonate by mass. The anhydrous form hits close to 100%, so fewer sacks deliver a stronger effect. I’ve watched frustrated maintenance crews open what looked like enough decahydrate for a big pool job, only to learn they needed twice as many bags. Not fun on a hot day.

Uses in Industry and Around the Home

Glassmakers swear by anhydrous soda ash because it melts fast and evenly. The water in decahydrate just steams off, wasting heat and energy. Detergent companies like the smooth mixing and measured dosing of dense, dry powder. In my experience helping at a swimming pool business, we used decahydrate for gentle pH tweaks because it dissolves at a steady, manageable rate, preventing sharp chemical shifts. It’s easier for adjusting chemistry a little at a time.

Cost and Practical Considerations

Hauling water makes decahydrate less attractive for bulk chemical buyers. You pay for what isn’t active soda ash, which eats into budgets fast. On the flip side, smaller doses or one-off use—like household cleaners or classroom labs—sometimes benefit from the easy, safe handling of softer decahydrate crystals. The risk of dust inhalation drops with the damper, chunkier variety.

Health, Safety, and the Environment

Anyone who’s dragged open a bag of anhydrous soda ash knows how the fine dust stings the nose and eyes. Even small amounts can irritate skin. Decahydrate is much friendlier; its moisture keeps dust down. No matter which you handle, gloves and eye protection still matter. Concerning chemical runoff, both break down the same way, leaving little environmental residue if used responsibly.

Moving Forward

Switching between forms boils down to a mix of handling needs, budget, and the job at hand. For bulk chemistry, shipping, or heavy industry, anhydrous soda ash rules the roost. Teachers, homeowners, or anyone looking for easier, safer handling often reach for decahydrate. Public education around the differences can trim waste and keep workplace accidents in check. Chemical suppliers can do right by retail customers through better labeling, weighing out the value of each option for the buyer’s real-life needs.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium carbonate decahydrate |

| Other names |

Washing Soda

Soda crystals Sal Soda Soda Solvay Sodium Carbonate 10-hydrate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm ˈkɑːbəneɪt ˌdɛkaɪˈhaɪdreɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 6132-02-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3587152 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32146 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201761 |

| ChemSpider | 52647 |

| DrugBank | DB11097 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.831 |

| EC Number | 207-838-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 62574 |

| KEGG | C01893 |

| MeSH | D013472 |

| PubChem CID | 61323 |

| RTECS number | VZ4050000 |

| UNII | X6SL7WCH0C |

| UN number | Not regulated |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2039248 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Na2CO3·10H2O |

| Molar mass | 286.14 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.46 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | soluble |

| log P | -6.19 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 15.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.62 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | '+2400.0e-6 cgs' |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.430 |

| Viscosity | Viscous solid |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 322 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1561.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2856 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A09AA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 2800 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 4090 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | VZ0950000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 200 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium bicarbonate

Sodium hydroxide Potassium carbonate Sodium sulfate |