Cupric Oxalate: Commentary and Insights

Historical Development

Back in the early days of inorganic chemistry, cupric oxalate didn’t exactly turn heads. Chemists experimenting with copper compounds studied it because copper easily forms beautiful salts. By the late 1800s, researchers began writing about its potential in analytical chemistry. The real spark came as scientists explored the basics of coordination complexes and the interesting range of copper’s oxidation states. Cupric oxalate went from being a curiosity to a lab staple, catching more attention as folks realized it could act as both a colorant and a source for nano-sized catalysts. Over the last fifty years, industrial interest in green synthesis reminded folks of oxalate’s gentle redox properties and its ability to act as a reducing agent without introducing halides or heavy acid waste.

Product Overview

You won’t spot cupric oxalate on store shelves, but it shows up across research labs and has industrial value. Chemically, you get it as a pale blue-green powder that doesn’t shout for attention, but its applications make people pay notice. Companies produce it for use in specialty ceramics, pigments, and niche catalyst manufacturing. Specification sheets matter to both the academic and industrial users because impurities can kill a reaction or skew lab results. Commercial sources usually sell it with purity grades above 98%, often mentioning moisture content and any trace metal contamination. Labeled correctly, you’re sure you’re working with the right stuff, and the label becomes a reference point for technical troubleshooting or regulatory compliance.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Cupric oxalate holds the formula CuC2O4. Water hardly budges it, but acids dissolve it quite well, which means powdered forms can last years on the shelf if kept dry. Its soft blue-green color looks dull compared to other copper salts, so artists ignore it. With a molecular weight close to 151.56 g/mol, it offers a decent source of copper ions for synthesis. Thermal decomposition is where it really gets interesting, breaking down around 200°C and releasing CO and CO2, leaving behind copper oxide. These decomposition products pose fuss for those not managing their ventilation. In the lab, its solubility lets it act as a soft-leaching source of copper, unlike copper sulfate. Chemically, it reacts readily with strong acids and bases, and crystalline forms show some nifty structural diversity under X-ray analysis.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

It pays to read and understand the technical data on chemical packaging. For cupric oxalate, suppliers list copper and oxalate content, drying loss, insoluble residue, and trace metal analysis. These specs aren’t fluff for the shelf; they prevent failed syntheses. Clear lot numbers and batch records tie directly to quality assurance and are required for regulatory audits, especially in pharma or advanced materials labs. Safety and transport labeling matter too, since copper salts can pose toxicity risks and must align with both local and international regulations. Every competent handler knows that ambiguous labeling ends up costing much more when something goes wrong.

Preparation Method

The standard route to cupric oxalate uses a water-based reaction between copper sulfate and sodium oxalate. The copper drops out as a fine blue-green solid, easy to filter and wash for high purity. Older manuals suggest that adding heat and careful pH adjustment helps maximize yield. Industry-level runs usually require filtration units that handle fine sediments to avoid losing product. After drying, you’re left with a solid fit for most applications. This synthesis process doesn’t generate much hazardous waste if handled properly, letting even small labs prepare their own supplies under decent safety practices.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

With active carboxylate groups and copper’s thirst for coordination, cupric oxalate fits into a long list of chemical transformations. Strong acids break it down, liberating oxalic acid and copper ions. In organic routes, oxalate acts as a mild reducing partner or a base for generating other copper salts. Under careful heating, it sheds its oxalate component, giving up CO, CO2, and copper oxide, which becomes crucial for generating nano-catalysts or ceramic precursors. Research pushes toward modifying its surface with organic molecules, tuning performance as a catalyst support, or leveraging its slow decomposition profile in advanced manufacturing.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll see “cupric oxalate” and “copper(II) oxalate” used interchangeably in English-speaking venues. Product codes at chemical suppliers might abbreviate it with formulas like “CuC2O4” or list it under broader categories such as “copper organic acid salts.” Other languages sometimes refer to it with local variations; in German and French catalogues, the root words change but point to the same substance. Consistent product names ensure researchers and buyers don’t end up with the wrong formulation, especially since copper(II) formate, acetate, and oxalate often cluster together in supplier databases.

Safety & Operational Standards

No one should take handling cupric oxalate lightly. Animal studies and workplace experience both make it clear that ingesting or inhaling this compound leads to copper poisoning and kidney damage. Oxalates can irritate skin and eyes, and once inside the body, oxalate ions run the risk of forming stones or crystallizing in tissues. Responsible operations keep spills and dust to a minimum. Proper gloves, eye protection, and fume hood use belong in every protocol. Companies caught shipping it without correct hazard labels face fines or worse if accidents occur. Waste routines require neutralization before disposal, since both copper ions and oxalic acid impact aquatic environments sharply.

Application Area

Experimenters and product developers look at cupric oxalate for more than just textbook chemistry. In ceramics, adding small amounts tweaks glaze colors and surface effects, but potters turn to more stable copper sources for bright hues. As an analytical reagent, its precise stoichiometry makes it valuable for teaching and quality control labs. Materials scientists eye it as a precursor to nano-sized copper oxide particles, prized for nearly every kind of catalysis, from water splitting to pollution breakdown. Battery research keeps it in rotation for anode preparation and performance testing. Some textile and wood preservative formulations include tiny amounts, mainly when resistance to mold or fungi matters, though the shift away from copper-based biocides continues in markets wary of environmental harm.

Research & Development

The last decade saw leaps in work using cupric oxalate as a starting point for more complex materials. Researchers lean into its thermal decomposition behavior to produce uniform copper oxide structures for use in conductive inks, solar materials, and sensors. Teams keep looking for lower-temperature preparation methods to save energy and avoid over-producing greenhouse gases. Studies looked at the coordination chemistry of cupric oxalate, crafting layered or polymeric forms with custom electronic and magnetic properties. There’s huge interest in developing composite materials piggybacking on oxalate’s ability to bind with organic ligands, opening doors for everything from greener anti-fouling coatings to biomedical imaging agents. Publication numbers keep ticking up, and major chemistry journals feature regular updates on copper oxalate’s modified and hybrid forms, especially as evidence grows that even small modifications can lead to big material breakthroughs.

Toxicity Research

Animal testing and human case reports hammered home the risks involved with handling copper oxalate compounds. Lab rodents exposed orally showed kidney and liver issues; oxalate ions contribute to the formation of dangerous calcium oxalate crystals in vital organs. Inhalation leads to chronic respiratory problems, and workers routinely exposed in chemical plants carry higher urinary copper and markers for renal stress. Regulatory bodies in Europe and the US monitor occupational exposure down to milligram levels. Researchers now design animal-free toxicity tests to speed up screening of new oxalate-derived materials and minimize animal suffering. Environmental researchers map out the compound's fate in water tables, finding that in some soils oxalate and copper bind tightly, cutting down the risk of leaching, but caution rules the day when planning new uses outside tightly controlled settings.

Future Prospects

Cupric oxalate won’t fade from the chemical landscape any time soon. Its cheapness and versatility keep it in the steady rotation for academic research and specialty manufacturing. Pushes for green chemistry keep the spotlight on its potential as a mild oxidant and as a precursor for copper oxide with low contamination profiles. As electronics shrink and demand for advanced nanomaterials grows, high-purity copper sources like cupric oxalate gain ground. Eco-labeling and regulatory pressure drive process chemists to refine recycling and waste neutralization. Safer synthesis methods, real-time toxicity monitoring, and nanotechnology likely build its case for broader adoption, as long as labs and manufacturers respect the hazards tied to copper and oxalate compounds. The balancing act between utility and toxicity will shape research and regulations in the coming decades, giving fresh relevance to a salt pulled from the old playbook of copper chemistry.

Diverse Roles of Cupric Oxalate

Cupric oxalate might not top many people’s lists of familiar chemical compounds, yet it plays quite a few roles in research labs and certain industries. Its vivid green color makes it stand out, but the real value comes from how it interacts with other materials. My time working in a high school chemistry prep room introduced me to a host of copper-based compounds. Cupric oxalate popped up the most during lessons on decomposition reactions and basic coordination chemistry. The way it transforms when heated always captured attention—students saw first-hand how heat can break apart a compound, producing copper oxide and carbon dioxide. That hands-on lesson stuck with more than a few teenagers.

Laboratory Chemistry and Research

Researchers turn to cupric oxalate when they need a pure source of copper ions without a strong acid or base mixed in. It fits into reactions where controlling the environment and pH means everything. In college, our inorganic chemistry lab featured cupric oxalate during a synthesis exercise. The compound worked well for this kind of work: it let us explore how transition metals bonded with different ligands, giving predictable results. Beyond college, scientists use it as a precursor for growing copper nanoparticles or thin films. This supports electronics research where precision matters and impurities can cause big headaches.

Ceramics and Pigmentation

Artists and industrial manufacturers value its striking color. Ceramics and glasswork studios blend cupric oxalate to create unique green hues. Unlike some pigments that fade or leach, copper-based oxalates offer stability under high heat, making the colors last longer in tiles or pottery. Friends who produce hand-thrown ceramics often tinker with different copper salts, including cupric oxalate, to dial in just the right shade without running into unpredictable chemical quirks in the kiln. That hands-on experimentation leads to more reliable results, and the stories behind each glaze recipe travel with the finished pieces.

Chemical Experiments and Analytical Work

Students and professionals working in analytical chemistry find cupric oxalate useful for calibrating instruments or teaching stoichiometry. Its known composition and fairly predictable decomposition mean fewer surprises, which is essential in a teaching lab. That’s something I remember from my early internships—senior chemists trusted compounds like this for standardization exercises or as a reference point for thermal analysis.

Challenges and Safer Practices

There’s no getting around it: even though cupric oxalate serves a clear purpose, it comes with health concerns. Like other copper salts, it poses risks—skin irritation, eye damage, and even more serious effects if someone swallows or inhales the dust. Stories circulate every year about students or hobbyists handling copper compounds without gloves or a fume hood. That careless approach can go sideways fast. Easy access to safety information, regular training, and safe disposal methods can keep accidents at bay. Proper labeling and locked storage also cut down on accidents or misuse outside the classroom or studio.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Cupric oxalate might seem like a niche compound, but it quietly enables breakthroughs, artistic creativity, and learning. Continued awareness of safer handling and creative uses matter just as much as the chemical properties themselves. The compound has earned its spot on the shelf, both as a teaching tool and a contributor to modern material science.

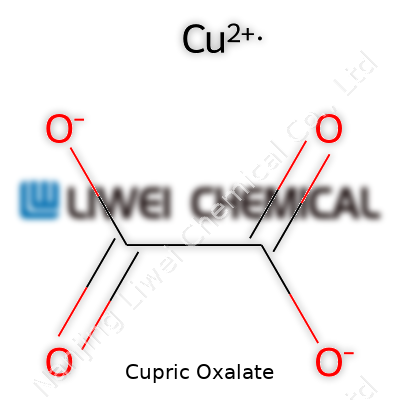

What is Cupric Oxalate?

Cupric oxalate stands out as a bright green, crystalline salt made of copper and oxalate ions. You’ll run into it mostly in chemistry labs or as a byproduct in some copper-related manufacturing. Someone who’s not in the science world rarely hears about it, but digging deeper into its risks matters to anyone around chemistry or materials processing. Its chemical formula—CuC2O4—may look simple, but the story that comes with it should not be ignored.

The Toxic Side of Cupric Oxalate

Both copper and oxalates have their own toxic effects. Throwing them together makes something that deserves a healthy amount of caution. The copper in cupric oxalate can disrupt critical processes in animal and human cells. Too much copper damages organs like the liver and kidneys and can upset the nervous system. Just farming families who treat crops with copper-based pesticides have documented cases of copper-related toxicity. Symptoms of copper overload cover stomach pains, nausea, vomiting, and confusion.

Oxalate brings its own risk, especially for the kidneys. High levels of oxalate, either from food or chemicals, form crystals with calcium inside the body. This usually shows up as kidney stones, but the worse outcome is kidney failure if exposure climbs too high. Cupric oxalate mixes these two hazards: excess copper plus the risk of oxalate buildup. Handling this green powder with gloves and masks doesn’t seem like overkill when you understand the toll on health.

Animal and Environmental Impact

Cupric oxalate harms animals the same way it does people. Livestock walking through soil contaminated with copper salts risk chronic poisoning. Farmers have watched sheep and cattle stumble from too much copper in their environment, even before synthetic chemicals became common. Dogs and cats can absorb it from licking or chewing objects. Even household pets shouldn’t be anywhere near open containers of laboratory-grade cupric oxalate.

This chemical doesn’t just threaten one species or one setting. If a lab spill leaks into waterways, copper ions poison fish and aquatic life. Studies show even “trace” copper levels slow fish growth, weaken immune systems, and stifle reproduction. Runoff from industrial use can transform a quiet creek into a dead zone. Real-world experience shows groundwater near some copper refining sites carries extra oxalate and copper, warning nearby communities to avoid untreated water for animals and crops.

How to Reduce Harm and Promote Safety

Respect for chemistry goes a long way in protecting workers, pets, and the environment. No one learns safety from facts alone; they learn from accidents, warnings on bottles, and personal stories. Every chemical, especially cupric oxalate, should stay in sealed, well-labeled containers. Proper ventilation, gloves, and goggles block the main entry routes. If a spill happens, it deserves attention right away using specific clean-up methods—usually wet cleaning, not vacuuming, since dry dust enters the air more easily.

Labs and industries that handle cupric oxalate must keep training people regularly. Disposal works best by sending waste to certified hazardous waste facilities. Never dump down the drain or into regular trash. Neighbors near chemical plants need clear communication from the company if contamination happens. Even outside the lab, shared habits—washing hands, locking up chemicals, and keeping animals safe—set a culture of caution.

Cupric oxalate looks harmless on a shelf but tells a different story when its risks come to light. Experience says that treating rare chemicals with care, not fear, lets science move forward without paying the price in health or environmental loss. Science protects us, as long as people respect what they don’t fully see—or think they know.

Understanding Cupric Oxalate in Everyday Terms

Cupric oxalate, which chemical enthusiasts and researchers recognize as copper(II) oxalate, pops up in both the lab and industrial world. Its formula is CuC2O4. This substance mixes copper’s distinct blue-green character with the organic bite of oxalic acid. You can think of it as a bridge between raw copper and the complex compounds found in nature and chemical manufacturing.

The Theory in Real Life

I recall the day I first handled cupric oxalate in a college lab. It appeared as a pale green powder—not the bright green folks imagine, but a subtle shade that makes you pause. Mixing copper(II) sulfate with oxalic acid in water, the resulting solid is tough to dissolve again. This trait ends up helpful for some applications, but it also means dealing with it requires care and a bit of patience.

Why Scientists and Industry Care

Cupric oxalate plays a quiet but important role across several fields. In organic chemistry, it steps in for specialized reactions, helping researchers make molecules that would be a pain to create otherwise. For pigment producers, its distinct shade anchors certain artist colors. It isn’t only scientists using this compound, though.

Many metal cleaners rely on oxalates to grab and dissolve unwanted rust. Here, copper(II) oxalate gets attention because of how oxalate ions break down iron(III) deposits. Wood preservation techniques have also borrowed from oxalic acid’s effect, though cupric oxalate itself sits on the edges, more as an example of copper chemistry’s reach.

Health and Environmental Facts

You won’t see cupric oxalate on grocery store shelves. Like many copper compounds, it does create safety concerns. Inhalation or accidental swallowing can irritate tissues, and copper build-up is no joke for the liver or kidneys. This isn’t an excuse to avoid all chemistry, but it serves as a reminder that materials like CuC2O4 need practical handling and clear storage rules.

Wastewater from factories sometimes carries copper and oxalate ions, making treatment vital. If left untreated, these ions harm aquatic life and possibly damage water supplies downstream. Decent cleanup means using technologies like precipitation, which removes copper ions from water, or advanced filters designed with environmental science in mind.

Responsible Use and Safer Alternatives

We can’t overlook the need for strict rules in labs and industry. Strong labeling, secure containers, gloves, and ventilation remain basic safety measures. Training for workers also reduces exposure risks. On the environmental side, it helps to recycle copper waste whenever possible and push for green chemistry processes that leave fewer leftovers.

Researchers have started looking at replacing traditional copper-based compounds with safer, less persistent versions in some applications. This move won’t happen overnight. Education and investment in new technology give the best shot at reducing risk while still producing the pigments, chemicals, and cleansers people depend on.

Staying Informed

Learning the chemical formula CuC2O4 gives a small window into the wider influence of copper chemistry. Staying informed about handling, safety, and waste treatment not only benefits those who use these compounds daily but also supports public health.

Understanding the Risks of Cupric Oxalate

Many chemicals demand respect, but cupric oxalate carries its own list of risks. On the surface, it appears as a green, crystalline powder, and that can fool even experienced technicians into underestimating what improper storage can trigger. It doesn’t take much mishandling for problems to start. A little moisture, unexpected heat, or a forgotten open container can start decomposition or pose health hazards. Anyone who has witnessed symptoms of copper compound exposure—nausea, headaches, breathing issues—knows why it pays to get the basics right.

Moisture and Temperature Matter Most

Dampness always seems to find its way into poorly sealed bags, jars, or bottles. Moisture isn’t just bad for the chemical’s stability. It can kickstart decomposition or convert cupric oxalate into substances you didn’t plan for. I’ve seen labs lose valuable batches simply because a screw cap wasn’t tight or a weather change snuck condensation into poorly sealed packaging.

Storage in a dry environment, away from humidity, makes a world of difference. Placing containers above the floor and away from windows keeps condensation and accidental spills at bay. Simple habits work—using desiccant packs, double-bagging, or tucking bottles in airtight plastic bins.

Heat is another silent problem. Even a few days above room temperature can help chemicals break down. Most laboratory storerooms control temperature, but I’ve known small schools to stash reactive chemicals wherever there’s shelf space—near radiators or hot water pipes. A thermometer on the shelf can reveal problems before damage happens.

Keep It Separated and Sealed

Cupric oxalate reacts with acids and even some common household chemicals. Storing it close to incompatible substances turns a mistake into a safety emergency. My old lab practiced color-coded bins and clear labeling, so mistakes happened less often. Copper compounds with acids or oxidizers multiply the risk.

Not every purpose-built chemical safe is outrageously expensive. Even solid plastic bins work if shelves are sturdy and labels are updated. Glass or heavy-duty plastic bottles with secure lids keep out air and prevent accidental spills. Shaking up dusty bottles releases small, invisible particles into the air. Wearing a mask and gloves takes seconds and protects anyone nearby.

Emergency Plans Save More Than Chemicals

Every safe storage routine benefits from regular inspections. Inventory checks help staff notice leaks, residue on containers, or a slow build-up of dust. Spills and cross-contamination often go unnoticed in dark corners or behind bottles. Dedicated disposal bottles and marked zones show everyone—including new students or employees—where to bring old or unused material.

Training doesn’t have to mean hours of wasted time. Short reminders about which gloves to use, how to check for damaged seals, or how to spot chemical changes strengthen daily routines. Having an emergency plan handy—posted on the wall with clear steps—makes a difference during real accidents.

Responsible Storage Means Safe Workplaces

Cupric oxalate forms just one part of any chemical shelf, but the principles for safe storage stretch across the lab. Diligence and attention to detail make chemical handling less stressful, especially in spaces shared with inexperienced personnel. A well-organized storeroom builds trust and prevents most emergencies before they start.

What Sets Cupric Oxalate Apart in the Lab

I remember the first time a chemist handed me a container marked "Cupric Oxalate." Right away, the powder’s delicate, blue-green color stood out. You see a lot of substances sitting on a chemist’s shelf, but few have that earthy tone. The coloring comes from the copper ions bound to oxalate, which actually hints at each molecule’s makeup before anyone even starts talking about how it behaves.

Texture, Structure, and What You Can Notice

Pick up a small scoop, give cupric oxalate a shake, and it acts like the fine powders you find in most university labs. Those grains don’t clump easily and feel a bit chalky to the fingers. What’s neat about this property—high surface area, zero visible crystals to the naked eye—makes it simple to spread out in water or to measure. This helps any researcher or industrial operator keep control over dosing and mixing.

Solubility and What It Means in Practice

Cupric oxalate resists dissolving in water. That means if you dump a pinch in a beaker and swirl, you’ll still find grains swirling around at the bottom, refusing to cooperate. But the story changes with the presence of acids or strong bases. Adding hydrochloric acid or ammonium hydroxide can coax a reaction and dissolve those stubborn grains. This isn’t just chemistry trivia. Knowing when a solid will stay put or break up comes up every day in the lab—especially for people working on copper plating, pigment manufacture, or even historic coin preservation.

Melting and Decomposition

I once worked with a team that heated copper salts hoping to draw out the pure metal. If you try this with cupric oxalate, you won’t get a nice clean melt. This compound starts falling apart before you reach melting temperature. Around 200°C, decomposition sets in—carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide escape as gases, leaving behind copper oxide. It gives a strong whiff of acid fumes, which calls for good ventilation. The lesson here: handling, storage, or disposal needs a careful setup, not just for safety, but also to keep the copper value intact.

Density and Handling Tips

The density sits at roughly 3.4 g/cm³. That’s on the heavier side for a powder, so it settles firmly in containers and doesn’t float around much when you pour. In the real world, that’s one less headache for handling. Very fine, lighter powders send little clouds into the air, irritating your throat and wasting material. Cupric oxalate's weight means less chance of inhalation and accidental contamination.

What the Data Means for Safety and Use

Properties aren’t just for textbooks. The low solubility, thermal instability, and density shape every step—shipping, storing, mixing. Long sleeves and gloves keep the skin safe, and working under a fume hood handles the hazardous fumes if you need heat. These steps grow from what the properties tell us. That’s how science moves off the page and shapes safety and productivity in the real world. As researchers, hobbyists, or industrial chemists, knowing these points means less surprise and less risk—something worth striving for in any workspace.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper(II) ethanedioate |

| Other names |

Copper(II) oxalate

Copper oxalate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkjuːprɪk ˈɒksəˌleɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 5893-66-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3860447 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:82274 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3306512 |

| ChemSpider | 14950 |

| DrugBank | DB16004 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 12c80e3d-b636-4e09-a911-5ece098b650d |

| EC Number | 205-027-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: 77677 |

| KEGG | C18659 |

| MeSH | D003558 |

| PubChem CID | 164859 |

| RTECS number | QU8140000 |

| UNII | H59V6KLH9W |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | CuC2O4 |

| Molar mass | 145.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | Pale blue-green powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.88 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | insoluble |

| log P | -7.71 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.37 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +1720.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.94 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 90.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -824.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -770.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V07AA |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, toxic if inhaled, may cause skin and eye irritation |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Harmful if swallowed. Toxic if inhaled. Causes skin irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Suspected of causing cancer. Causes damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P321, P330, P332+P313, P333+P313, P362+P364, P391, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-2-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 410°C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 780 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 780 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WX8570000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 0.1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 200 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Cuprous oxalate

Copper(II) carbonate Copper(II) acetate Copper(II) sulfate Iron(II) oxalate |