Copper Picolinate: Untangling a Trace Mineral Compound

Historical Development

Long before anyone thought about copper’s role in biochemistry, folks recognized how copper kept water fresh or made tools last longer. Only over the last few generations did scientists start isolating copper complexes to harness distinct health or industrial benefits. The story of copper picolinate follows the boom in nutritional science during the late twentieth century, when curiosity about micronutrients ramped up. As research moved forward, explorers in the field found that picolinic acid, a byproduct in the body, could tightly bind copper ions, making it a promising candidate for targeted delivery and absorption. The compound moved from lab oddity to catalog staple, finding its way into research kits, supplement markets, and materials science discussions. Following interest from the nutrition industry, regulatory bodies and academic labs started cataloging the characteristics and uses, annotating each step of the way with deeper insight.

Product Overview

Copper picolinate presents itself as a blue-green crystalline powder, sometimes distributed under the guise of dietary supplements or as a niche laboratory reagent. Interest in this complex often centers on bioavailability, driven by folks looking to sidestep poorly absorbed copper salts. In supplement form, the material flatters labels focused on supporting enzyme function and red blood cell formation. Digging into other sectors, copper picolinate’s chelating behavior brings new opportunities to fields like analytical chemistry, where predictable reactions with other metals give solid, reliable measurement results. Not limited to pills, this compound steps into explorations of agriculture, advanced materials, and occasionally electronics.

Physical & Chemical Properties

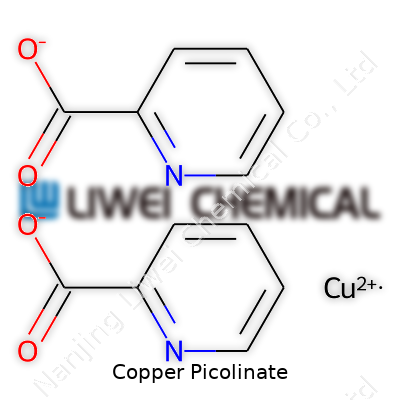

Pull a scoop of copper picolinate under a strong light, and the eyes pick up a distinct blue-green, hinting at its metal core. The powder usually stays dry under normal storage but picks up moisture if left exposed too long. With a molecular formula of C12H8N2O4Cu, copper picolinate combines two molecules of picolinic acid with a single copper(II) ion at the center. This structure controls its solubility—dissolving better in acidic water and less so in neutral or saline solutions. The molecular weight clocks in around 327 grams per mole, allowing chemists to calculate dosages or yields without much hassle. The crystal structure resists thermal breakdown up to moderate temperatures, but it breaks apart with strong acid or base, a pointer to how it might behave during digestion or industrial use.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Products hitting the market list copper picolinate by strict purity percentages, often above 98%, tracing back to pharmaceutical or food-grade standards. Labels need to spell out the copper content per serving in the case of supplements, often measured in micrograms or milligrams—a legal requirement in places like the EU and the US. Analytical certificates step up documentation, providing data on heavy metal contaminants, water content, and residual solvents. Containers usually warn away children and recommend refrigeration or dry, cool storage to keep decomposition low. In the industrial catalog, manufacturers attach information on batch traceability, recommended handling gear, and shelf life expectations.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers create copper picolinate by reacting picolinic acid—commercially sourced or derived from niacin pathways—with copper(II) salts such as copper sulfate or copper acetate. The process favors aqueous solutions where pH sits around neutral, helping both ligands and ions meet without excess side products. Stirring and controlled heating encourage the components to join, forming a blue-green solid that drops out of solution. After filtration and washing to remove leftover acid or copper, drying takes place under vacuum or gentle heat, readying the batch for packaging. Lab-scale notes emphasize maintaining cleanliness and avoiding iron contamination, as trace metals change the color or purity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Copper picolinate stands out for its chelating properties, driven by nitrogen and oxygen atoms in picolinic acid linking snugly to copper(II). The stability of this bond makes it robust against simple exchanges in water, but high acid or base disrupts the complex, partitioning copper ions into free form or into other coordination networks. In more advanced organic synthesis, scientists test copper picolinate as a mild catalyst for oxidative coupling reactions, leveraging its capacity to shuttle electrons without harsh side effects. Chemical tweaking, such as substituting different alkyl or aryl chains onto the picolinic backbone, shifts solubility or reactivity, which gets attention for designing targeted reagents or improving uptake for specific applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

In catalogs and research papers, copper picolinate appears under many names—copper(II) picolinate, cupric picolinate, bis(picolinate)copper(II), and sometimes as brands with proprietary blends in the supplement world. Some global regions favor shorthand, while others prefix the molecular formula or vendor codes for traceability. These synonyms cut across pharma, chemical supply, and consumer health segments, sometimes causing confusion but always pointing back to the same chelated core.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling copper picolinate safely means keeping eyes open for both chemical and toxicological hazards. On the chemical side, direct skin or inhalation exposure can irritate sensitive folks. Workers typically wear nitrile gloves, goggles, and lab coats during preparation or weighing. Regulatory agencies, including OSHA in the US and its counterparts abroad, expect documentation and risk assessments for raw materials and finished goods, especially when products target ingestion. Limits on dust, spill cleanup, and ventilation trigger detailed training protocols. Storage means avoiding excess heat and locking away from food. In supplement production, manufacturers watch for cross-contamination and adhere to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) rules, with batch testing and reporting tied to both health and environmental safety.

Application Area

Copper picolinate’s utility branches out from health supplements, where advertised benefits touch on everything from immune health to connective tissue repair. In research labs, the compound picks up experimental roles—serving as a copper source in trace element studies, calibrating analytical machines, or stabilizing certain bioactive peptides. Agriculture studies test copper picolinate for plant fortification, judging its impact on growth or disease resistance. Outside life sciences, attempts to harness copper’s conductive or catalytic power in green chemistry and electronics seed new ideas for waste recycling, water purification, and nano-coating technologies.

Research & Development

Research teams dig deep into how copper picolinate absorbs compared to other copper supplements. They track markers in blood, test micronutrient interactions, and study enzymes in cell cultures. Some studies suggest better uptake, while others find marginal differences based on individuals’ gut environments. Beyond nutrition, synthetic chemists look for ways to swap out copper for other metals, tuning picolinate complexes to deliver drugs or bind pollutants. Automation in testing and analytics lets labs check stability in dozens of environments, giving heads-up on shelf life or storage tweaks. Larger R&D outfits investigate copper picolinate’s physical structure, hoping to tune particle size or surface area for non-nutritional uses, such as flow batteries or low-energy electronics.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity sits under the microscope for every copper compound, and copper picolinate follows suit. Animal and cell studies catalog safe dose limits, mapping what happens when copper collects over time versus single exposures. Short-term studies look at stomach upset and liver enzyme changes, while longer studies chase neurological and systemic impacts. Reviews roll copper picolinate under the wide umbrella of copper exposure, noting that people with Wilson’s disease or existing copper overload face the highest risks. Regulatory authorities set upper intake levels based on collective data, urging oversight, especially for vulnerable groups. These findings feed directly into supplement labeling, where warnings and disclaimers reflect the latest science and case reports.

Future Prospects

Looking down the road, copper picolinate might shed its supplement-only image. Material scientists chase applications that blend copper’s electrical and biochemical traits, targeting smart sensors and bioactive devices. Agriculture researchers keep hunting better delivery methods for micronutrients, fighting soil depletion and boosting crop resilience with less waste. As the food tech sector zeroes in on precision nutrition, copper picolinate could work alongside other tailored minerals, answering demands for customizable health products. Ongoing research into chronic toxicity and pharmacokinetics will settle debates on long-term safety, opening the door to wider pharmaceutical or cosmeceutical uses. Each step ties back to hard science, lived experience, and the evolving rules that keep these compounds both useful and safe.

Understanding Copper Picolinate

Copper picolinate stands out to many folks interested in nutrition. It’s a supplement form of copper, bound to picolinic acid, which the body absorbs well. Copper, as a mineral, shapes healthy blood vessels, nerves, immune responses, and bones. Food brings in copper just fine for most people, but picky eating or specific health issues can leave gaps. I’ve talked with people who struggled with chronic fatigue, skin issues, and weak immunity—some found real change after getting their copper situation checked out and addressed through supplements like copper picolinate.

The Crucial Role in Health

Copper helps enzymes put oxygen where it belongs, manage iron, and clear out free radicals. Its role in energy creation and mental clarity shouldn’t be overlooked. One study, published in the journal Nutrition Reviews, emphasized copper’s part in brain development and memory. The absorption boost from picolinate might let those short on copper get back on track faster than standard mineral pills.

Shortfalls in copper sometimes happen more than you’d think, especially in people living with celiac disease, kidney issues, or heavy reliance on processed foods. Symptoms—fatigue, brittle bones, poor immunity—can sneak up without warning. Doctors may spot low copper through blood work, and sometimes suggest supplementation. Nutritionists tend to push for food first—nuts, beans, greens—but copper picolinate supplements offer a more targeted approach when food isn’t enough or absorption’s an issue.

Who Looks for This Supplement?

Long-distance runners, women with anemia, and those working on vegetarian diets often want to keep their mineral status in check. These folks rely on lab results and professional advice, because extra copper isn’t always wise. Too much copper can harm the liver or interfere with zinc levels. I saw a case where someone tried stacking lots of mineral supplements to get more energy, only to land in the doctor’s office with stomach pain—personal curiosity needs a partner in science and smart dosing.

Fact-Checking Benefits and Risks

Even though marketers love to hype supplements, reliable evidence shapes smart choices. Research by the National Institutes of Health notes copper supplements can benefit people with clear mineral deficiencies. Copper picolinate offers ease of absorption, but science still sorts out whether it beats other forms like copper gluconate or sulfate in all cases. Brands may make big promises, but not every claim stands up when peer-reviewed.

Plenty of experts highlight the tightrope walk: the line between replenishing nutrients and pushing the body too far. Signs of too much copper—a metallic taste, stomach cramps, or mood swings—should send people back to a doctor’s office, not further down the supplement aisle. Testing before starting, following up with feedback from real health practitioners, and focusing on diet all help keep copper levels right where they belong.

Supporting Healthy Choices

It makes sense to double-check nutrient intake if fatigue, immune bumps, or memory shifts crop up. Copper picolinate isn’t a quick fix or a solo superstar, but it does hold value for those with a real need and solid guidance. More voices in the health world push for lab-confirmed deficiencies, evidence-based supplementation, and honest conversation between patients and their health team. Keeping track of symptoms, eating a range of whole foods, and thinking about all nutrients as a team effort—these habits keep wellness goals within reach, without falling for hype or over-supplementing.

Understanding Why Copper Matters

Copper plays a role in making red blood cells, supporting the immune system, and helping the body turn food into energy. Some days I notice how much smoother things go with my energy and concentration when my mineral intake stays balanced. Missing key nutrients like copper over time can sneak up on people. Low copper sometimes leads to fatigue or weak immunity, especially for folks eating restricted diets or relying heavily on processed foods.

The Unique Side of Copper Picolinate

Copper picolinate delivers copper in a form that the body absorbs efficiently. Using this supplement appeals to people who might have gaps in their diet, like people eating plant-based or taking high doses of zinc which can lower copper. The appeal also grows among those who find themselves dealing with unexplained tiredness or poor wound healing, and discover their copper levels dipped after bloodwork.

How to Figure Out Dosage

Healthcare professionals often suggest a daily intake for adults around 900 micrograms from all sources, food included. Most copper picolinate supplements provide small amounts – usually under 2 milligrams. If a doctor recommends copper, always check the serving size on the label. Too much copper, especially above 10 mg each day, can start causing upset stomach or, over time, lead to liver issues. I try to remind friends to stay clear of high-dose copper unless a doctor directs them.

Safe Ways to Add Copper Picolinate

Best time to take a copper supplement lands between meals. Iron and zinc supplements can interfere with copper getting absorbed, so I usually suggest folks avoid mixing these. A glass of water helps carry copper through the digestive system more smoothly. Checking with a healthcare provider makes sense, especially for pregnant people or those already taking a multivitamin with copper.

Food Still Comes First

I grew up learning that a plate rich in nuts, seeds, leafy greens, and shellfish generally provides enough copper. Supplements should step in only when diet falls short or when lab tests show a clear gap. Seafood lovers, people eating a lot of chocolate or organ meats often get more copper naturally, so adding supplements on top won’t help much and can sometimes push levels too high.

Keep an Eye on Symptoms and Bloodwork

People sometimes make the mistake of pushing through nausea or discomfort, thinking it’s just their body getting used to supplements. Symptoms like stomach pain, vomiting, or yellowing of the skin ask for immediate attention. Routine checkups and bloodwork tell a clearer story on copper status than how someone feels day to day. I usually encourage people to share every supplement they're taking with their doctor—clear communication paints a full picture.

Supporting Claims with Facts

Data from the National Institutes of Health shows true copper deficiency comes up most often in those with digestive issues or on restrictive diets. Zinc supplementation can lower copper absorption, which doctors account for when making recommendations. Studies also connect long-term overuse of copper supplements to liver problems and weakened immune response.

Solutions and Smarter Supplement Use

Start with a conversation with a healthcare provider—someone trained to interpret nutritional bloodwork and consider the full supplement list. Focus on food choices rich in copper. Only use copper picolinate supplements if testing finds a need, always following the professional’s suggested dose. Store supplements out of reach of kids and keep labels handy for every appointment. Healthy habits put copper back in balance for most people without reaching for a pill bottle every day.

Understanding the Risks

Copper shows up in breakfast tables, cereal boxes, and even the vitamin aisle. Nutritionists talk about it for energy, blood health, and keeping nerves sharp. With so many copper supplements out there, copper picolinate has carved a spot on wellness blogs as a form touted for its higher absorption. It’s tempting to believe you can pop a pill and tick off a nutrient box. The reality carries more layers, especially around side effects.

The Human Body and Copper Balance

Copper isn’t just another mineral; it works in small amounts to help enzymes power reactions in every cell. Too little, and nerves, immune system, and blood might suffer. Too much, and copper turns toxic fast. Kids learn in science class about “trace minerals.” The tricky part is dosage – our bodies need a tiny fraction to run well, barely a milligram daily. Most folks reach that by eating nuts, legumes, and seafood. Supplements step in where diets fall short, yet it’s easy to overshoot the mark.

Common Side Effects

Many who have tried copper picolinate haven’t noticed big changes right away. Some only realize something’s up after a few days: an off stomach, nausea, perhaps cramps after a heavy meal. At higher intakes, copper overload could start to show up as vomiting, diarrhea, or even a metallic taste in the mouth.

In my own experience, a multivitamin with copper seemed harmless until I stacked on another supplement for “brain health.” Within a week, I woke up feeling queasy and had odd blue-green stools. My doctor nailed it down to too much copper. The thing is, even a health enthusiast like me forgot to add up minerals across different supplements.

Long-Term Dangers of Excess Copper

Long-term use raises the stakes. Excess copper can build up, especially for anyone with a liver problem. Blood work might pick up anemia, as copper crowds out zinc and iron absorption. Symptoms can look like low mood, brain fog, or joint aches—things that get written off as stress. Studies link copper overload to increased risk of liver and kidney damage. Everyone should get labs checked before reaching for extra minerals, especially anyone with Wilson’s disease or autoimmune troubles.

Supporting Reliable Use with Evidence

Look at the science: the National Institutes of Health recommends only about 900 micrograms of copper a day for adults. That’s less than most people realize. The FDA has flagged copper’s potential to cause toxicity if supplements are overused. The European Food Safety Authority caps supplement levels at 5 mg for daily intake, well below many commercial capsules. These are not arbitrary warnings. They come from studies of people ending up in the ER after too much copper.

Smarter Solutions For Safe Supplementing

Label reading makes a difference. Check the serving size and copper percentage. Take only what your doctor suggests after bloodwork. Let lab results guide, not fear of “missing out.” Nutritionists suggest food first: leafy greens, shellfish, and beans. If a deficiency diagnosis lands, work with a provider to add just enough copper, not more. Skip fancy blends and aim for simplicity. Remember, more isn’t always better.

Looking Ahead

Supplement manufacturers hold responsibility too. They should list copper forms and doses, follow third-party testing, and shape ads around real science, not buzzwords. It isn’t just about checking a box—health grows from balance, not shortcuts.

Copper in the Body: More Than a Trace

Most folks rarely think about copper, except when they spot the green on old pennies. Yet, there’s more riding on this mineral than you might guess. I learned this the hard way, years ago, after burning out and barely scraping by with energy. Bloodwork showed my copper skimming the basement. It’s not alone, though—about a third of Americans don’t meet daily copper needs, given modern food processing and mineral-depleted soils.

Absorption: More Complex Than Labels Suggest

Supplement shelves offer copper in many jackets: gluconate, sulfate, bisglycinate, picolinate, and the classic oxide. Each claims superiority in absorption. Copper oxide often ends up least effective; our guts struggle to extract copper from that rock-like form. Gluconate and sulfate fare better, but they still face competition from other dietary minerals—especially zinc and iron—when crossing into the bloodstream.

Copper picolinate comes into focus here. Picolinate refers to the acid attached to copper, thought to help usher minerals across intestinal walls. Picolinic acid, as found in some supplements, has a track record helping zinc and chromium slip over the gut barrier, which led to speculation about copper getting the same boost.

Research and Real-World Evidence

Hard data on copper picolinate, though, remains thin. Few published human trials compare picolinate to gluconate, sulfate, or bisglycinate head-to-head. Some test tube studies hint at improved uptake, and animal research shows picolinate can lift copper levels efficiently. Still, if absorbing copper was just about chemical attachments, us nutritionists could make recommendations without hesitating.

But absorption depends on gut health, diets rich in phytates (think whole grains and legumes), and other minerals taken at the same time. Real people can have great absorption with gluconate, and others see no jump with picolinate. Each person’s gut, stress level, and even coffee habit can tilt the balance.

Why This Matters

Low copper leads to trouble: weak immunity, struggling energy, even nerve problems or anemia. I’ve seen it especially among athletes on zinc-heavy regimes, vegetarians, and folks with GI issues. Skimping on copper starves enzymes that keep nerves firing, bones strong, and hearts beating evenly. On the flip side, overdoing copper supplements can backfire—too much puts a load on the liver and can trigger unwanted symptoms.

Thoughtful Solutions, Not Hype

Looking for the “best” copper form risks missing the bigger picture. If digestion’s humming and diets aren’t loaded with zinc, people usually do fine choosing most reputable forms, like gluconate or bisglycinate. Picolinate deserves more research before crowning it king. Seeking out a doctor’s input before supplementing makes good sense, as lab tests highlight real needs. For those with true copper deficiency—diagnosed, not guessed—a paired food or supplement strategy, not a one-size-fits-all pill, gives the best shot at restoring balance.

Better farming practices and more plants on the plate help too. People chasing health trends sometimes forget that minerals work as a team; chasing one in isolation leaves out the orchestra. Every time I see another fancy copper supplement hit the shelves, I remember those burned-out years. Solutions belong in small habits, open conversations with healthcare providers, and a plate heavy with real food—not just a trendy capsule.

Looking Closer at Copper Picolinate

Copper picolinate often shows up on health store shelves. The promise of better energy, strong immune function, and even healthy skin sells itself. Many supplements float under the radar, and people often pop them without thinking twice about what else they’re swallowing that day. Experience with supplements over the years has taught me that “natural” never guarantees “harmless.” Interactions can sneak up, especially when it comes to trace minerals like copper.

Interaction Risks in Everyday Use

Copper doesn’t just wander through your body on its own. It dances with other nutrients and medications. For example, zinc and copper ride the same absorption train in the gut. Take too much of one and the other gets pushed aside. More than one study has shown high zinc supplements can drop copper levels, risking deficiency symptoms like fatigue and memory troubles. The competition between the two is real. Doctors recognize this—zinc therapies for Wilson’s disease purposely block copper.

Iron tells a similar story. Iron and copper team up inside red blood cells to form hemoglobin, but too much copper can tip the balance, impacting iron’s job. If someone takes an iron supplement along with copper, getting the dose right matters. Too much copper can make iron absorption drop, possibly driving anemia in some people.

Supplements don’t live in a vacuum. Blood pressure medicines (like ACE inhibitors or diuretics) can change the way your kidneys handle minerals. Adding copper picolinate to a big medication list stacks up the chances of a hiccup. Certain antibiotics, such as tetracyclines and penicillamine, can grab copper or change its absorption, which means either the antibiotic or copper ends up less effective. Nobody taking heavy-duty antibiotics for infection wants to risk treatment failure because a supplement blocked its work.

How Real People Get Blindsided

In my community, it’s common to see patients reach for supplements before asking their doctor. The logic makes sense—“It’s just a mineral.” But behind the counter, pharmacists see cases where a new supplement throws off a stable medication routine. Older adults using multivitamins, osteoporosis medicines, thyroid pills, or even birth control can wind up with their test results out of whack, all because nobody thought to ask, “Do these two things play nice together?”

Easy access to online health advice can sometimes give folks the wrong impression. There’s a sense that if you stick to “normal” doses, nothing can go wrong. But people vary—the way a 25-year-old marathon runner’s gut absorbs copper looks different from a sixty-year-old with heart disease and chronic kidney problems.

Raising the Bar on Safe Supplement Use

Keeping medication and supplement lists current gives doctors and pharmacists the best shot at spotting trouble. It’s worth asking about new supplements, and honest conversations around side effects and over-the-counter health habits help catch problems early. Websites with up-to-date interaction checkers—like MedlinePlus and the NIH’s Office of Dietary Supplements—let people double check before starting something new. Testing for copper and other mineral levels only makes sense if someone has symptoms, or their doctor sees red flags.

Supplements offer benefits, but only for folks who need them. Copper’s role in human health deserves respect, but not a free pass. Taking the time to weigh the good with the possible risks keeps people healthier—and may save a hard lesson later on.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | copper(2+) bis[(pyridine-2-carboxylato)N,O] |

| Other names |

Copper(II) picolinate

Copper dipicolinate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒp.ər paɪˈkɒl.ɪ.neɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 93699-11-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 4303563 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:86379 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3986617 |

| ChemSpider | 20771494 |

| DrugBank | DB11271 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 05be2d42-5238-4d7d-9797-58a20d7f6c57 |

| EC Number | 263-048-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 173145 |

| KEGG | C05248 |

| MeSH | D013812 |

| PubChem CID | 6433203 |

| RTECS number | GL7440000 |

| UNII | DFV0B3ZIG4 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C12H8CuN2O4 |

| Molar mass | 309.68 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light blue to blue-green powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.79 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | -1.8 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.0 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.85 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.63×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.677 |

| Dipole moment | 2.92 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 334.5 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1165.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX14 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary Statements: P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): >5000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Copper Picolinate: "Oral, rat: 1,000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | Not Listed |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 1.1 mg per day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Zinc picolinate

Manganese picolinate Chromium picolinate Copper gluconate Copper sulfate |