Copper Methionine: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Copper methionine did not appear out of nowhere; its origins trace back to the growing awareness that animals often struggled to properly utilize inorganic copper in their diets. Early feed supplementation focused on simple copper salts like copper sulfate, but these compounds faced criticism for poor absorption, digestive irritation, and unpredictable results in livestock and poultry. Researchers in the 1970s started looking at chelated minerals, inspired by the way vitamins and amino acids improved nutritional outcomes. Methionine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, proved to be a fitting ligand for copper, producing a compound that animals readily absorbed. This line of thinking led to a wave of research that has only become more intense. Today, copper methionine acts as a standard in feed supplementation, especially as pressure grows to get more productivity from less input and reduce environmental copper loads.

Product Overview

Copper methionine shows up in the market as a blue-green powder or granulate, sometimes pressed into tablets or contained within premixes for industrial feed. You will find this product in the catalogs of global feed additive companies, usually as copper(II) bis(methioninate). Suppliers offer boasts of better bioavailability and reduced antagonism with other dietary components. While humans may not encounter this compound on the dinner plate, its footprint runs through poultry, swine, aquaculture, and dairy operations. Many nutritionists vouch for its positive impact on animal growth, feathering, reproductive functions, and disease resistance.

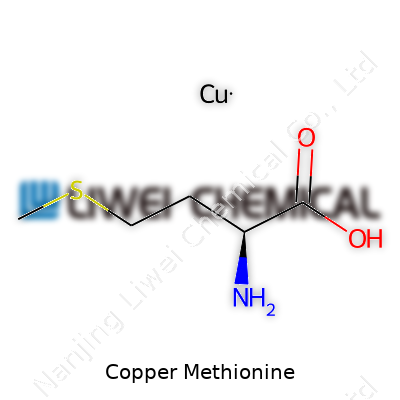

Physical & Chemical Properties

The compound forms deep blue or green crystalline structures, thanks to copper’s coordination effects with methionine’s sulfur and amine groups. Its molecular weight lands around 387. Its solubility trends fit chelated forms—appreciable in water but not as rapid as copper sulfate. The odor ranges from neutral to faintly amino, with a melting point surpassing many simple amino acid complexes. Pure samples avoid caking and clumping if protected from humidity. Like other copper products, extended storage in moist conditions can promote slow hydrolysis.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers declare copper content, typically not falling below 20% by weight. Labels reference methionine content, moisture percentage, and bulk density. Good suppliers include heavy metal screens showing low levels of lead, arsenic, and mercury. Technical sheets outline both organic and total copper content, salt ratio, and recommendations for blending into complete feeds. Directions emphasize formulating to meet species-specific requirements since over-supplementation risks copper toxicity. Producers active in the European Union must reference feed additive regulations (such as Regulation (EC) No. 1831/2003) for each label. North American suppliers tend to highlight compliance with AAFCO guidelines.

Preparation Method

Industry comfort with amino acid chelates means you’re not going to see household kitchen methods in use. Copper methionine production involves reacting copper(II) salts with L-methionine under controlled pH (neutral to slightly alkaline) in aqueous medium. Operators watch temperature and agitation closely to promote chelation, followed by filtration and evaporation to produce solid crystals. Final purification steps filter out unreacted copper and free methionine. The whole process often unfolds in food-grade stainless reactors and ends with vacuum drying or spray drying, producing a dust-free fine powder ready for bagging or bulk shipment.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Copper methionine stands out because its copper atom sits in a tight embrace with two methionine molecules through nitrogen and sulfur atoms. Normal dietary acids or neutral salts don’t break this tight chelation easily, so it survives passage through the acidic environment of the stomach. You can, if motivated, drive the dissociation back toward copper(II) salt and free methionine under strong acidic or basic conditions, but this rarely happens outside lab beakers. The product can combine with other micro-minerals in multi-chelate blends, though its stability profile is best with dry, neutral components. Few other modifications see industrial scale, as adding extra functional groups rarely improves absorption and only increases cost.

Synonyms & Product Names

The feed and chemical industries refer to copper methionine using several familiar terms. You’ll encounter names like copper bis-methionine, copper(II) methioninate, or copper methionine complex. Some suppliers call the product ‘chelated copper methionine’ or ‘organic copper methionine’ on their trade catalogs. A few variations use labels that highlight brand identity alongside core terminology, but the essential product stays the same. CAS Number 8013-05-4 identifies this family of substances in most regulatory documents, technical sheets, and research papers.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling copper methionine safely doesn’t differ much from procedures for most feed-grade copper compounds. Dust control matters, as fine powders can irritate respiratory passages. Gloves and masks stay within reach for operators, who avoid unnecessary skin contact to lower any chance of rash or copper sensitivity. Workspaces remain clean, with emphasis on preventing accumulation around bagging areas. Feed facilities in the U.S., EU, and elsewhere face regular audits to prove compliance with Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) and GMP+ manufacturing codes. Safe storage conditions—cool, dry, and away from acids—help maintain product quality and keep staff and animals safe.

Application Area

Copper methionine’s reach stretches across the livestock and animal nutrition industry. You see it blend into rations for poultry, where it supports feather formation and egg production. Dairy cattle feeds use it for bolstering hoof health and the reproductive cycle. Swine nutritionists turn to copper methionine to spur weight gain and keep gut health on track, especially as blanket antibiotics phase out of commercial rations. Aquaculture relies on this source to combat copper deficiencies in fast-growing fish species. Even pet food producers experiment with copper methionine for canine and feline diets that aim for improved coat quality and immune health. Sustainability managers lean on its higher absorbability, letting them cut total copper loading in manure, meaning less risk of heavy metal build-up on farmland.

Research & Development

Academic studies continue to compare copper methionine against both inorganic and alternative organic sources. Trials with broilers show higher serum copper levels and better growth metrics compared to sulfate forms. Dairy studies link copper methionine to stronger immune status and less hoof disease. Investigations continue into how copper chelates influence gut microbiota and impact disease resistance under commercial stressors. Feed mills and biotech firms collaborate to refine chelation efficiency, work on encapsulation for better stability, and verify that copper appears in the tissues where animals need it. Researchers in environmental science track manure copper excretion and are mapping its impact on soil microbiomes.

Toxicity Research

Copper methionine earns positive marks for safety, but that doesn’t allow for complacency. Excess copper, regardless of form, builds up in the liver and poses a threat, especially to sheep and some dogs. Trials routinely determine a threshold beyond which copper supplementation becomes a liability, with early signs including reduced appetite and jaundice. Research confirms that methionine chelation lowers acute toxicity compared to copper sulfate, mainly due to better cellular control over copper uptake, yet strict adherence to dose recommendations remains critical. The animal nutrition community, through its journals and continuing education forums, stresses regular blood and tissue monitoring in long-term feeding strategies.

Future Prospects

People in the feed industry expect copper methionine to remain a central player as scrutiny builds around both environmental impact and animal health. Regulatory agencies call for lower copper limits in manure, and producers press for supplements that work at lower total doses but still deliver performance. Companies continue investing in better chelation technology, improved traceability, and finer control over impurity profiles. There’s room for innovation in functional blends—combining copper methionine with other amino acid chelates or antioxidants for holistic benefits. What stands out is that this compound, born from decades-old ideas about nutrition, finds itself at the cutting edge of precision livestock feeding, where every new study brings both hope and challenge to the next generation of animal production.

Why Animals Need Copper Methionine

Growing up on a small farm, I saw firsthand what happens to livestock when diets come up short in key minerals. Copper kept popping up as a critical one. Animals lacking this mineral show rough coats, lose their appetite, or stop growing well. The truth is, not all copper supplements give the same results. That’s where copper methionine steps in.

This supplement ties copper to methionine, an essential amino acid. Animals absorb this form much better than simple copper salts because their bodies recognize the natural structure and grab what they need. Getting enough copper in this form supports enzyme systems, builds strong immune responses, and keeps tissues healthy and growing.

Striking Differences in Animal Health

I have seen dairy cows with brittle hooves start bouncing back after diets included organic trace minerals. Poultry in commercial houses lay stronger eggs with better shells. In piglet barns, adding the right copper sources helps fight off diarrhea and keeps growth rates strong. Skeptics can check published studies — animals fed copper methionine often show better weight gain and greater feed efficiency than those on traditional copper sulfate.

On the science side, copper works inside enzymes like cytochrome c oxidase, which keeps cells working day in and day out. Breeders care about this because stock that grows slowly or looks poor costs everyone in the chain: the animal, the farmer, the industry, and even consumers who pay higher prices for meat, milk, and eggs.

Challenges With Mineral Nutrition

Many people assume tossing cheap mineral salts in animal feed solves every deficiency. What ends up happening is much of that copper passes right through and never gets absorbed. It ends up in manure and can cause headaches for people managing land for crops. High levels of unabsorbed minerals also stress the environment, raising questions about sustainability in the livestock business.

Veterinarians and nutritionists now look for ways to improve the absorption of every mineral. Copper methionine shines here — less goes in the feed, more gets used by the animal, and less passes into the soil. Fewer deficiencies mean healthier herds and flocks, and farmers spend less money fixing problems that trace back to poor nutrition.

Ethical Choices and Better Outcomes

No one wants to overuse additives or pile up costs that don’t give returns. But using a form of copper that animals use better keeps supplements reasonable and results consistent. Some countries even place limits on total copper in feed to keep farms in line with environmental laws. Choosing forms like copper methionine becomes less about quick gains and more about responsibility to the land and animals.

As the livestock world leans on technology and research, the focus shifts to smarter feeding — giving just enough, in the best form, and paying close attention to every outcome. That’s not just science; it’s common sense gained from years spent in muddy boots and barns where results matter more than labels or marketing.

Aim for Smarter Solutions

It pays to look beyond simple cost per bag and ask about results in the barn and field. Talk to people living with the animals every day. Putting copper methionine in the mix has brought real benefits — real improvements in growth, health, and even long-term profits. Smarter nutrition plans backed by research and field experience deserve attention, not just from experts but anyone who wants a healthier, more sustainable food chain.

Understanding Copper Methionine

Copper methionine blends copper, an essential mineral, with methionine, an amino acid found in protein-rich foods. Feed manufacturers and supplement makers use this compound because it can get copper into the body in a way that is easy to use. In my years working on a small family farm, I saw plenty of feed bags labeled with copper methionine, especially those meant for dairy cattle, poultry, and even pets. Both animals and humans need some copper to keep enzymes working and support growth. Too little can stunt development or harm immune responses.

Why Dose and Source Matter

The story always comes down to how much copper gets into the diet and the source it comes from. Plants and meats both supply copper, but the body can struggle to absorb enough—even with a diet designed by experts. Adding copper methionine can solve a shortage, but it’s easy to tip the balance too far. Farmers who add multiple supplements sometimes run into problems when copper builds up in the liver. In sheep, for example, too much copper leads to toxicity, causing anemia or even sudden death. Cattle and goats handle extra copper a bit better but still suffer if fed for long periods at high levels.

People need much less copper than animals. Most folks eating a balanced diet pick up enough from food—whole grains, seafood, nuts, and organ meats stay top sources. Health authorities like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority have clear limits for copper intake, usually about 0.9 mg a day for adults. Supplements can help if a doctor finds a true deficiency, but extra copper won’t cure most problems and could cause stomach pain, nausea, or worse over time.

Scientific Backing and Concerns

Science supports the use of copper methionine as a reliable mineral source. Research journals and universities point out that this form of copper gets absorbed better than basic copper sulfate, leading to improved growth or egg production with less copper waste in manure. A published trial in the Journal of Dairy Science even showed dairy cows getting more benefit from copper methionine versus basic copper salts.

Still, copper methionine doesn’t work miracles. I’ve heard of hobby farmers assuming that because a supplement works in a lab, it’ll triple their animals’ growth. But too much of a good thing will backfire. A field veterinarian once told me of sheep herds poisoned by mineral blocks intended for cattle, all because the copper content was right for one species but wrong for another.

Safe Use in Feed and Diet

It boils down to using copper methionine thoughtfully. Anyone raising animals can benefit from regular lab tests, not guesswork. A quick blood or liver test points out shortages before adding anything new. For people, choosing real food over supplements usually stands as the safest bet. Copper methionine may show up in some human multivitamins, but real risks remain rare unless someone ignores recommended daily intakes or has an underlying liver problem.

I’ve learned to respect both the power and the danger in mineral supplements. Keeping track of mineral levels and sticking to established guidelines mean the animals eat well and avoid risk. For both livestock and folks, copper methionine generally helps—if managed with common sense and a willing eye for the facts.

Why Copper Methionine Matters in Nutrition

Copper Methionine doesn’t get much attention compared to other trace minerals, but it plays a big role in animal nutrition. Many producers, nutritionists, and farmers use it to help support good growth, immune health, and fertility in livestock. From my experience working with producers, I’ve seen how easy it is to overlook copper supplementation. Animals showing poor coat quality or strange gait sometimes don’t get copper from their main feed, and Copper Methionine—because it links copper to an amino acid—gets absorbed better than just raw copper sulfate.

What the Science Says

For cattle, research from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine points to requirements somewhere between 10-15 mg of copper per kilogram of dry matter intake each day. By using Copper Methionine, a producer often needs less total copper compared to inorganic sources thanks to its higher absorption rate—some studies put this usage down to 6-10 mg/kg dry matter. Dairy cows usually get recommended about 100 to 200 mg Copper Methionine per head daily, but this depends greatly on forage quality and base ration mineral content.

Pig nutritionists often shoot for 4-6 mg per kg body weight, daily—though commercial diets often top out at 25 mg total copper per kg feed from all sources for grower-finisher pigs (with Copper Methionine making up just a piece of the whole contribution). Chickens and other poultry tend to have copper needs around 8 mg/kg feed, but most integrators adjust this, knowing the balance between trace mineral sources—the chelated form helps especially where gut health takes priority.

Risks and Toxicity

Too much copper brings danger. I’ve seen it firsthand: Lambs and some cattle show signs of poisoning—yellow mucous membranes, sluggishness, and sudden deaths—when dosed even slightly over safe limits, especially if their baseline feeds already run high in copper. Consulting a nutritionist often helps avoid the headache of oversupplementation. Genetic differences in breeds and differences in soil content all play a part. Regular lab tests, even just annual, remove a lot of the guesswork and lower the risk.

Mixing Copper Methionine with other minerals brings up competition: molybdenum and sulfur impact copper absorption, sometimes making it look like requirements have increased. Feeding programs in the American Midwest, for instance, must factor in water and forage mineral content.

Suggestions for Practical Use

Producers benefit from a close relationship with their feed mill and vet. Don’t assume all mineral blocks or premixes give the same amount per serving—labels sometimes cause confusion, especially between elemental copper and total product. My routine involves watching for warning signs in animals and never skipping regular bloodwork for copper status.

I recommend researching university extension resources and using nutritionist-designed calculators. Adjusting Copper Methionine dosage always counts as part of the bigger mineral plan. A one-size-fits-all approach rarely works. Staying aware of changes in breed, management, and local forage can mean the difference between healthy, efficient animals and hard-to-solve health problems.

Looking Forward

Demand for chelated mineral sources like Copper Methionine isn’t a trend that’s fading. As science continues digging into mineral bioavailability, recommendations may shift, but prioritizing animal health, careful measurement, and a clear understanding of the numbers will always serve best.

How Nutrition Shapes Animal Health

Copper helps animals grow well, keeps the immune system working, and supports normal reproduction. As a lifelong livestock owner, I’ve seen what happens when animals don’t get enough trace minerals—thin hair, weak legs, and sluggish behavior. Not every source of copper works the same, though. Animals often struggle to absorb it from standard feed minerals, and that’s where copper methionine steps in.

The Real Value Behind Copper Methionine Supplements

Copper methionine stands out because it joins copper to methionine, an essential amino acid. This bond means more copper gets into the animal’s bloodstream. Compared to copper sulfate or oxide, absorption rates jump up. Studies with calves and chickens have shown that copper methionine helps build strong bones, thick coats, and faster weight gains, using less total copper in the feed. So, this supplement not only improves animal well-being but can also lower mineral waste—something feedlots and dairy operations care about for both cost and environmental rules.

It’s easy to overlook how much mineral content influences farm profit. Years ago, I noticed the heifers on a copper-rich supplement didn’t get sick as often after weaning. I later learned that copper helps fight off common infections by keeping blood cells working efficiently. Nutritional research from major universities continues to connect proper copper intake with improved disease resistance and more efficient feed use.

Environmental Pressure and Smarter Feeding

Traditional mineral mixes often lead to much of the copper passing through manure. This can cause problems, especially for farmers on tight nutrient management plans. Regulatory agencies are getting stricter about copper runoff, which can contaminate ponds and soil. Because copper methionine lets animals absorb more copper, farmers can give smaller doses to get the same benefits. That cuts the risk of stressing pastures and water supplies. Conservation-minded ranchers see this as a win-win—better animal health and smaller environmental footprint.

Balancing Cost and Long-Term Gain

Some argue that copper methionine costs more than standard mineral blends. This is true at face value. But feed budgets run deeper than just ingredient price. Sick animals require more vet visits, grow slower, and may even lose value at the sale barn. By keeping herds resilient and productive, investments in bioavailable minerals like copper methionine can pay off in better performance. Research from livestock extension services backs this up, showing lower rates of lameness, diarrhea, and reproductive setbacks in herds with good copper nutrition.

Not every farm or animal needs the same mineral program. Testing for copper status makes sense before jumping in. Still, for flocks, herds, or pets under stress, with high growth demands, or facing disease, copper methionine offers a practical solution. Farm experience, together with animal nutrition science, has shown it can play a key role in moving toward more precise, humane, and sustainable agriculture.

Practical Advice for Supplementation

If you raise animals yourself, work with a qualified nutritionist or local extension office. Test forage and water sources, as soil chemistry and water quality can interfere with copper use in the body. For many operations, adding copper methionine in balanced amounts can boost productivity, cut health costs, and maintain a better environment. Stronger animals, cleaner land, and steady profits—those benefits mean more than a line on a feed label.

Why Copper Methionine Draws Attention

Copper methionine gets a lot of attention in animal nutrition and food supplements. It's a combination of copper and methionine, an amino acid, which together aim to improve copper absorption in the body. Many nutritionists recommend chelated minerals like copper methionine, saying they may be easier on the digestive tract and better absorbed than old-school sources like copper sulfate. Farmers and pet owners often choose this chelated form, believing it can lead to healthier animals, shinier coats, and better immunity.

Recognizing Side Effects and Risks

No additive comes without a few concerns. Even though copper plays a crucial part in animal health, too much can cause real trouble. Studies show copper toxicity leads to liver damage, issues with red blood cells, and even death in severe cases. Sheep, for example, carry a high risk of copper poisoning—they don’t handle excess copper the way cattle or goats do. Chronic exposure, even in small doses over time, piles up in the liver and spills out suddenly with life-threatening consequences.

Some supplement users believe organic complexes like copper methionine completely solve these worries. Research disagrees. The body might absorb copper methionine better, but overdoing it still causes the same problems as other forms. Several academic reviews and veterinary case reports detail animals accidentally poisoned after using premium copper products, including methionine chelates.

Human Use Raises Questions

Copper methionine sometimes shows up in human supplements, especially in blends targeting athletes or “biohackers.” Side effects in people look similar to those seen in animals—nausea, stomach pain, and in extreme cases, jaundice and organ damage. For someone with Wilson’s disease, even small copper doses bring severe risk. Sometimes, gut bacteria or other dietary factors make things worse by messing with absorption or metabolism.

There’s also real debate over whether anyone in a developed country needs extra copper. U.S. diets already offer enough through nuts, seeds, shellfish, and leafy greens. For most, gains seen from copper methionine supplementation remain unproven, while the possibility of going overboard stays a genuine concern.

Paying Attention to Dosage and Sources

Specialists recommend careful dosing above all else. The difference between help and harm stays razor thin with copper. For livestock, labs test feed and tissue to fine-tune how much copper goes in. Good record keeping on each batch of feed avoids accidental overdose. Feed mills often consult published maximum tolerable levels and double-check calculations.

People thinking about supplements should talk to their doctor and, if possible, request copper blood tests before starting anything new. Supplements come with quality variation, so working with brands that show third-party testing or certifications helps dodge contamination and dose errors.

What’s Worth Focusing On

Nobody questions the value of trace minerals like copper, but story after story in veterinary clinics and research journals shows what happens if people lose sight of the basics. Know the animal, measure the diet, and treat supplements with careful respect. In human health, respecting personal needs, talking with physicians, and remembering that “more” doesn’t mean “better” stays the best path forward. Copper methionine holds promise, but only for those who keep risks in mind at every step.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper(2+) bis[(2S)-2-amino-4-(methylsulfanyl)butanoate] |

| Other names |

Copper Amino Acid Chelate

Copper(II) Methioninate Copper Methionine Chelate Copper bis(methionine) |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒpər mɛˈθaɪəniːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 14025-21-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 2584591 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:85199 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL613193 |

| ChemSpider | 13336598 |

| DrugBank | DB14597 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 05a3e7f6-7870-427f-b4f7-d2c601fcdfb0 |

| EC Number | 222-885-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 285893 |

| KEGG | C19652 |

| MeSH | D017936 |

| PubChem CID | 24870122 |

| RTECS number | BP9090000 |

| UNII | Z3Z94R9D6E |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020527 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Cu(C5H10NO2S)2 |

| Molar mass | 337.89 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light blue to blue crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | ~0.9 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.94 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.28 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 1.54 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 199.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -373.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CX04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07; GHS09; Warning; H315, H319, H335, H411 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat) > 2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2,700 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | Not established |

| PEL (Permissible) | 1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Methionine

Zinc Methionine Manganese Methionine Copper Sulfate Copper Glycinate |