Copper(I) Acetate: Insight into an Old Compound with Fresh Perspectives

Historical Development

Stories about copper compounds rarely grab the headlines, but their influence stretches from alchemists' workshops to modern chemistry laboratories. Copper(I) acetate, sometimes called cuprous acetate, first found attention centuries ago. Early chemists often stumbled onto it through experiments with vinegar and copper coins. Over time, the formula CuC2H3O2 matured into a known entity. The relationships built around copper’s affinity for oxygen and acetic acid present one of those foundational stories in the history of redox chemistry. By the nineteenth century, European scientists established reproducible protocols for its synthesis. This era seeded not only chemical knowledge, but also a generation of copper-based pigments used in textiles and ceramics.

Product Overview

Copper(I) acetate crystallizes into light greenish to reddish powders, a result that hints at its two-faced chemical nature. It serves as both a learning tool and a workhorse in synthesis. The material shows limited stability in air, changing to green copper(II) salts over time, so keeping samples dry matters. The commercial product today appears in pure, analytical, and technical grades. Chemists reach for this compound during couplings, reductions, and organometallic reactions. Available in small glass-stoppered bottles or customized bulk orders, each container comes tightly sealed. Modern packaging focuses on limiting moisture ingress and oxidation.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The physical character of copper(I) acetate draws as much from its color as its surprisingly low solubility in water. Its melting point sits around 115°C. The powder compacts easily, with a faint vinegar smell on first opening. Density averages close to 1.93 g/cm³ and it dissolves well in solvents like acetonitrile. As for chemistry, the compound adopts a polymeric structure featuring ‘paddlewheel’ dimers typical for copper(I) carboxylates. Chemically, Cu(I) prefers to hang on to its lone s-orbital electron, making this compound an effective reducing agent in some settings. Exposed to air, it oxidizes at the surface; the inside can hold its character for weeks if kept sealed.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Every label on laboratory copper(I) acetate highlights purity, manufacturer, and batch. High-grade options clock above 98% purity and list trace contaminants like iron or chlorine at ppm levels. Talking safety, labels mark ‘toxic if swallowed’ and include globally harmonized system (GHS) hazard pictograms. Suppliers include storage advice: tightly closed containers; limits on temperature swings; no contact with acids or oxidizers. For trace analysis and sensitive reactions, the certificate of analysis comes stapled right to the carton, laying out water percentage, copper content, and residual acetate. For export, customs identification numbers and United Nations shipping codes make the journey smoother.

Preparation Method

The laboratory route starts with copper(II) acetate and brings in a mild reducing agent—often sodium nitrite or copper metal itself. Chemists stir a solution of glacial acetic acid and copper oxide, sustaining gentle heat. Inert atmospheres play a central role here. If made outside a glovebox, oxidation creeps in, and the final product takes on a muddier color. Precision in this procedure yields better product. Filtering and careful drying—sometimes in a desiccator—make a massive difference in shelf life. Homemade preparations never seem entirely free of mixed-valent copper ions, so analytical chemists check each batch.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Copper(I) acetate unlocks many synthetic doors. In the realm of organic chemistry, it’s a catalyst for Ullmann-type couplings, where aryl halides get converted into biaryls. It also plays a part in azide-alkyne cycloadditions, the famous click chemistry that’s reshaping how drugs get designed. The compound will convert to copper(II) acetate with just a whiff of damp air. Mix it with ligands like phosphines, and it forms complex catalysts. In reactions with alkynes, it enables acetylide formation—a trick useful in both lab-scale and industrial syntheses. You find it modifying the structure of other organometallics and even bridging into coordination polymers with unusual properties.

Synonyms & Product Names

Copper(I) acetate travels through history under many names. Beyond ‘cuprous acetate,’ it’s gone by ‘acetic acid copper salt’ and ‘copper ethanoate(I).’ Chemistry stores catalog it as ‘Copper acetate, monovalent,’ while some textbooks use the name ‘copper(I) ethanoate.’ Regulatory listings feature codes like UN3077—touching on hazard status for transport. Synonyms might seem trivial, but missing them can delay supplies or prompt costly mis-shipments. Good research always starts by double-checking these names.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling copper(I) acetate demands focus. Even minuscule amounts can cause stomach upset or, in larger doses, organ damage. Long sleeves and gloves serve as the main barrier. Proper fume hoods help lessen inhalation risks. Regulatory frameworks spell out best practice, with both OSHA and REACH guidelines laying down the law for storage and disposal. Solutions get disposed of as hazardous waste, never down the drain. Good training programs stress quick response if spills happen—grab the spill kit, avoid clouding the air, and limit skin exposure. Facilities that use copper(I) acetate at scale maintain clear protocols for first aid and exposure reporting, never leaving newcomers to figure out safety on their own.

Application Area

Industry puts copper(I) acetate to work in syntheses for pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals. The click reaction in drug pipelines leans heavily on its catalytic efficiency. Some agricultural fungicides emerge from copper acetates, though the monovalent version plays a smaller part. Electronics manufacturing sometimes reaches for it in copper nanoparticle production. In academic labs, experiment after experiment treats this compound as a gatekeeper to more complex molecules. The dreamy green-blue pigment found in antique murals owes partial thanks to its relatives, a nod to art's unspoken partnership with chemistry. Material scientists continue testing how copper(I) acetate fits inside microstructured batteries or flexible circuits.

Research & Development

Research teams pick copper(I) acetate for role in new catalysts, especially those that support sustainable, low-energy chemical transformations. Peer-reviewed articles track its place in greener synthetic routes: less waste, fewer byproducts. Its potential for organic-inorganic hybrid materials gets attention in journals on nanoscience. Through industry partnerships, universities have used it to chart out new classes of MOFs—metal-organic frameworks. The hunt for cost-effective solar cells often weaves this copper salt into solution-based deposition techniques. Grant proposals pitch its use in streamlined routes for aryl amine synthesis, cutting out harsh reagents and lowering energy bills.

Toxicity Research

The copper story often revolves around its biological toxicity. Extensive animal studies chart threshold levels below which no harm shows up. Chronic exposure, even at low levels, can cause liver or kidney strain. Cellular research pinpoints copper(I) as a disruptor of some enzyme systems, which partly explains its value in fungicides but also signals risk for humans. Occupational health studies recommend strict airborne concentration limits. Evidence from laboratory accidents confirms eye and skin irritation at the point of contact. Toxicology labs report on environmental persistence and impact, finding copper ions can upset aquatic life, forcing factories to guard wastewater.

Future Prospects

Looking forward, copper(I) acetate sits inside a broader conversation about green chemistry and resource management. Academic groups continue searching for more stable analogs that share its reactivity while lasting longer in storage. Innovation in packaging and microencapsulation may soon extend the shelf life on industrial scale. Its use in materials science, especially as a seed for elaborate catalysts or a precursor for electronic inks, draws funding and publication. Regulatory scrutiny, sparked by its toxicity profile, ensures that use becomes ever more targeted—less waste, fewer environmental releases. The story remains unfinished, bolstered by ongoing work bridging classic chemistry and state-of-the-art applications.

Unpacking a Simple Compound With a Significant Role

Copper (I) acetate, better known in many labs as cuprous acetate, has a straightforward formula: CuC2H3O2 or Cu(CH3COO). This compound brings a faded green shade to mind, not the bright color that pops up with copper (II) approaches. Working with different forms of copper, I’ve learned that each tells its own story in a bottle. This salt often gets overlooked, but it deserves more attention than it gets.

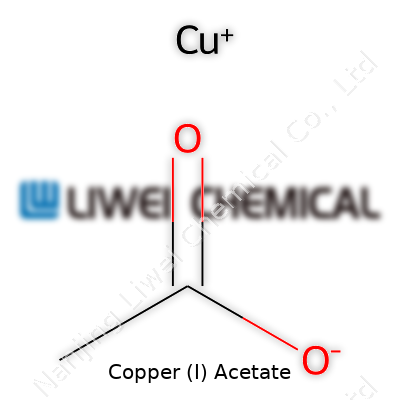

Structure Matters in Chemistry

Copper usually carries a charge of +2 in most compounds. Here, it goes with a +1 charge, which changes how it reacts and behaves. That makes copper (I) compounds like this one less common in everyday chemical storage rooms. Most encounters, at least on my workbench, involve the blue-green copper (II) acetate, yet the color and properties shift with just a tweak of oxidation state. If you hold a vial of copper (I) acetate, you’re holding something that can react in ways its cousin simply won’t.

Practical Uses and Real-World Relevance

Over years of mixing and matching reagents, I’ve leaned on copper (I) acetate mostly as a facilitator in organic synthesis. Its job? Often it helps create new bonds between two particles that won’t shake hands on their own. This matters when speed and yield push every reaction. In the world of electronics, copper (I) acetate makes its way into thin film coatings and as a precursor to other copper-based materials. Manufacturers chasing better solar panels and sensors eye it for how it drops copper atoms right where they’re needed.

The Hazards and How to Handle Them

Working with any copper salt means you think about safety. Back in undergrad, someone in my lab got a nasty scare from mishandling a related compound. Copper compounds can irritate skin, eyes, and lungs. With copper (I) acetate, contact burns are rare but not impossible. Breathing in any powder brings thunder from the safety officer’s office. Good practice: gloves on, mask ready, keep it contained and wash up right after. Throwing waste copper salts down the sink doesn’t fly — heavy metals make their way into water, and cleanup isn’t cheap or easy.

Science Education: Seeing Chemistry In Action

Years ago, a teacher handed out samples of copper (I) acetate for a demonstration with organic compounds. Students’ eyes lit up — not just at color changes, but from seeing reactions leap off the page. Using cuprous acetate in labs can demystify redox chemistry and help beginners spot what a jump in oxidation really means. Real hands-on chemistry, with safe steps in place, matters for building a basic respect for laboratory science and the people working in it.

Finding Balance: Storage, Disposal, and Sustainability

Industry and schools face pressure to reduce chemical waste. That’s a struggle I’ve watched firsthand, from small labs up to big factories. Any excess copper (I) acetate should go to a hazardous waste handler. Labs that keep raw chemical use low, batch by batch, avoid sitting on bags of unused material — good not just for safety, but for the bottom line. Teaching smart handling builds trust between lab staff and the environment they work in. Green chemistry isn’t just a buzzword; it’s the future for anyone who wants to keep both their lab and their conscience clean.

Why Copper (I) Acetate Finds Its Way Into Labs and Industry

Copper has played a role in chemistry and industry for centuries. Among its many compounds, Copper (I) Acetate has its own set of practical uses thanks to its specific chemical behavior. Day-to-day users might never come across a jar of this greenish powder, but for researchers and manufacturers, it makes a quiet difference in many projects.

Organic Synthesis: Shaping Useful Molecules

Chemists appreciate Copper (I) Acetate as a gentle introduction of copper ions into reactions. The compound appears most often in organic chemistry labs, not just because it is available, but because it brings reliability. In making complex molecules, especially those involving small tweaks to carbon rings, it steps in as a catalyst. Certain carbon-carbon bond forming reactions, such as Ullmann-type couplings, become more efficient when this copper salt is around.

People developing new drugs or agricultural substances often rely on these reactions. Copper (I) Acetate helps them avoid harsher chemicals or more expensive alternatives. Its action guides the right atoms together and lets chemists run reactions under milder conditions—having worked in a research lab, I remember times when swapping to this copper compound kept sensitive parts of a molecule safe.

Precursor to Other Copper Compounds

Some industries use Copper (I) Acetate as a stepping stone to other copper compounds. It offers a controllable path to products like copper(I) oxide or copper(I) chloride, both of which play roles in electronics, ceramics, or pigments. Copper (I) Acetate dissolves fairly well in certain solvents, making it easier to produce these other materials without lots of leftover residue.

Material Science & Electronics

Copper (I) Acetate isn’t shaping the outer shell of your phone, but it does help in research striving for better electronic materials. Scientists studying semiconductor properties reach for this compound to grow specialty crystals and thin films where copper introduces interesting electronic effects. These experiments inch closer to new types of solar cells or faster transistors.

Colleagues who focus on thin film deposition have shared how copper acetate feeds a carefully controlled process. The compound's unique mix of copper in the +1 oxidation state keeps reactions from veering off course. The success or failure of a thin-film project sometimes rests on how cleanly and predictably each layer forms.

Historic and Decorative Uses

Copper (I) Acetate once helped make pigments, especially “verdigris” for artists and decorators. Painters sometimes chose verdigris for its range of blue-green shades. Although modern pigments have mostly taken over the art world, some traditionalists and restoration experts still turn back to this time-tested copper salt.

Challenges and Safer Practices

Handling copper salts isn’t risk-free. Copper (I) Acetate can irritate skin and lungs if dust goes airborne. It makes sense for labs and workers to rely on gloves, eye protection, and good air systems. There’s room to reduce environmental impact by improving containment and reuse methods. Using less toxic solvents in reactions and boosting recycling efforts can cut down on waste.

Harvard released a guide in 2021 outlining safer handling of copper compounds—a resource worth checking out for anyone in the trenches of chemical research.

Looking Ahead

Copper (I) Acetate probably won’t land in mainstream headlines, yet its behind-the-scenes roles keep industry, research and even rare art projects moving ahead. With ongoing advances in green chemistry and better waste handling, its use can grow even safer and more sustainable.

Everyday Applications and Real Risks

Walk into a chemistry lab, and there’s a fair chance you’ll bump into a bottle labeled “Copper (I) Acetate.” Its deep green hue often catches the eye, but curiosity shouldn’t outrun caution. This isn’t something to play around with, and based on my own experience in research labs, even chemicals that aren’t notorious like mercury or cyanide still demand careful respect.

Copper (I) Acetate, or cuprous acetate, lands somewhere in the mid-range of chemical hazards. It’s awarded a Health Hazard Level 2 by the globally standardized NFPA diamond, signaling that health effects can’t be ignored. Skin or eye contact leads to burns or irritation—sometimes severe. Breathing in even moderate amounts of dust can leave you coughing and scrambling for fresh air. I recall a post-grad co-worker, a seasoned chemist, who absentmindedly touched a reagent bottle and ended up with an annoying but educational skin rash. He’d handled worse but learned the copper salts aren’t as harmless as they look. Proper gloves and good ventilation end up just as important as the actual experiment.

Toxicity Beyond the Lab

Copper in small doses builds strong bodies, but copper salts—particularly in soluble forms—pack a punch that no one wants. According to safety data sheets and GHS (Globally Harmonized System) labeling, swallowing copper (I) acetate causes nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, with larger doses leading to liver or kidney distress. More than one documented poisoning occurred after someone mistook a copper-based compound for a food additive or supplement—a mistake that never ends well. For the curious, eating pennies won’t do much (beyond a stomachache), but a mouthful of this powder could put someone in the ER.

Breathing in copper (I) acetate as dust or powder brings specific risk for lung irritation. Chronic exposure—rare outside of industrial settings—can result in a condition known as metal fume fever. Workers handling copper salts in manufacturing must stick to respirators and regular health checks for a reason. OSHA and NIOSH agree that occupational exposure limits for copper dust or mist protect workers from cumulative harm.

Respecting Environmental Impact

Cleanup doesn’t just mean tossing used beakers in the sink. Copper compounds, flushed or discarded carelessly, seep into waterways and land up in soil where plants and aquatic life absorb them. Copper pulls double-duty—an essential trace element yet toxic in excess. Pollution can kill fish or damage crops. Regulatory bodies like the EPA classify copper runoff among substances requiring close monitoring.

Sensible Handling and Safety Steps

Knowledge turns dangerous substances into manageable ones. Anyone using or storing copper (I) acetate should invest in basic protective gear. Gloves, goggles, and an apron create solid barriers. The simple rule of not eating, drinking, or smoking in the lab reduces accidental poisoning risks. Spill kits and neutralizers—like citric acid for copper spills—aren’t expensive, but they save headaches.

Waste disposal picks up where safety gear leaves off. I’ve learned it’s always worth double-checking local hazardous waste guidelines. Small efforts, such as keeping copper salts in properly labeled, sealed containers and arranging pickups by certified handlers, make a tangible difference. Even students in teaching labs catch on quickly after a safety briefing and a stern warning.

Learning from Experience

People interact with copper (I) acetate for all sorts of reasons—teaching, research, manufacturing chemicals, or even as a catalyst in specialty processes. What matters most is keeping eyes open for the real risks, sticking with best practices, and treating those green crystals with the same respect as more notorious hazards. The knowledge is out there, the safety rules work, and a little discipline goes a long way, both for personal safety and care for the world outside the lab.

The Real Deal With Copper (I) Acetate

Anyone who spends time around chemicals knows copper (I) acetate’s blue-green tint signals more than drama in a beaker. This compound’s reactive nature can surprise even experienced chemists. Stable copper (I) compounds easily jump to copper (II) if they meet a little too much air or moisture. Those who have watched a batch turn colors in unexpected ways get an unwelcome reminder: conditions in the storeroom matter.

Where Trouble Starts: Air, Light, and Moisture

A powder like copper (I) acetate picks up water from the air. Dampness acts like a silent button, triggering changes you want to avoid. Many folks shrug at exposure, figuring a sealed jar blocks everything. But steamy basements, leaky windows, or over-air-conditioned labs create microclimates tough on bottle contents. Once, after a humid week, a jar labeled “fresh” showed a clumpy cake at the bottom—signs of slow reaction with the air, not a supplier mix-up. Clearly, dry air makes a difference.

Sun and fluorescent bulbs also cause trouble. If copper (I) acetate stands on a sunny shelf, its surface can darken as it oxidizes. Old lab techs point out that jars left in the open near windows change color faster. Covering containers with amber glass or keeping them away from direct light heads off these surprises.

Avoiding Headaches: Practical Storage Tips

No need for a fancy vault. A dry, cool cupboard with minimum temperature swings usually does the trick. Many labs use desiccators—simple boxes with drying agents at the bottom—to hold a handful of reactive salts. Silica gel beads or anhydrous calcium sulfate work well. If you feel the crunch of silica in a packet, the jar around copper (I) acetate won’t see much moisture. Some researchers mark jars with the date they opened the container, making rotation and regular checks part of the workday routine.

Tightly fitting lids block out damp air, but thin plastic wraps or loose stoppers don’t last long. More than once, I’ve seen folks wrap uncovered jar tops with parafilm or a tape seal, so prying hands or careless movement doesn’t risk contamination from dust or splashes in crowded storage areas.

Keep the Workplace Safe

Storing chemicals always comes back to health. Inhaling copper dust or touching the powder without gloves causes real harm—no one wants green stains on their skin or a sick stomach after a hasty cleanup. Place copper (I) acetate away from acids or materials that release chlorine; these combinations turn unpredictable. Familiarity leads to routines: storing only what’s needed, labeling shelves, keeping the chemical inventory updated. This approach helps anyone, from students up to research directors, who may share workspaces and supplies.

Fact sheets and safety data sheets give guidelines, but real experience shows the value of practical habits. A dry jar, an airtight lid, a shaded shelf, and attentive labeling—the simplest steps keep chemicals stable, preserve their usefulness, and protect everyone down the line.

The Look of Copper (I) Acetate

Copper (I) Acetate doesn’t announce itself with a bold presence. In its purest form, it turns up as a white powder. Leave it lying around in air, and a subtle transformation takes place. You start to notice a greenish tinge creeping in, thanks to some fresh oxidation. This is one of those moments where chemistry reveals its personality—Copper (I) doesn’t feel comfortable out in the open, and oxygen coaxes it to shift its hue. Truth be told, you probably won’t find a sparkling white mound outside a well-sealed container.

The shape isn’t dramatic either. There’s no twinkle, no crystals that catch your eye. It simply collects as powdery, nearly chalky stuff. If you open a bottle of old copper (I) acetate, that pale green might remind you of antique coins or weathered statues—small hints of copper’s affinity for the atmosphere.

Physical Properties That Matter

The melting point lands around 115°C, which is fairly low compared to other copper compounds. This means you won’t need to break out a blast furnace to make it shift from solid to liquid—important for any hands-on chemist or teacher handling experiments at the bench.

It resists dissolving in plain water. Toss it in and you’ll just end up chasing clumps with a glass rod. That said, it does interact with concentrated ammonia and other complexing agents, forming solutions with characteristic blue shades from copper’s other forms. As for smells, there’s nothing distinctive here—no sharpness, no vinegar. So you work with it by sight, not scent.

Most people working with this compound will note its sensitivity to light and air. Let it sit on a watch glass, and exposure turns it from white to green as it oxidizes all too quickly. This means you need to store it tightly closed and preferably in a dark place if you want to maintain its true identity. Experience in teaching labs taught me the frustration of going for pure copper (I) acetate only to discover it’d quietly shifted colors in the bottle, a lesson in why chemical storage truly matters.

Why These Details Make a Difference

Chemists rely on these properties when predicting reactions and planning experiments. That unwillingness to dissolve in water nudges experimenters to reach for different solvents. That low melting point suggests careful handling, especially for those using hotplates. Its habit of oxidizing easily means you pay attention to storage and handling more than you might with more stubborn compounds.

This doesn’t just stay in the laboratory. Anyone working in the production of specialized chemicals faces those same quirks. Quality control folks watch for the telltale green sign of oxidation. I’ve seen quality slip when people weren’t careful about light or airtight storage, leading to contaminated batches and wasted raw material. That’s money down the drain for any manufacturer.

Reliable Practices for Using Copper (I) Acetate

To keep it in peak condition, store it in sealed, opaque bottles, away from direct sunlight and damp conditions. Work quickly, cap bottles tightly, and keep your workspace dry. If you handle it for educational or research purposes, always check for color changes before use. Waste less, save money, keep results accurate—good habits make the difference.

People sometimes ask whether it’s dangerous to handle. Like many copper compounds, it isn’t something you want to eat, inhale, or rub into your skin, but with basic gloves and a dust mask, it isn’t hard to handle responsibly. As with any fine powder, a little respect goes a long way.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | copper(I) ethanoate |

| Other names |

Acetic acid, copper(1+) salt

Copper acetate Cuprous acetate Copper monoacetate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒpər wʌn əˈsiːteɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | [598-54-9] |

| Beilstein Reference | 3581397 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:51756 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3584878 |

| ChemSpider | 21833 |

| DrugBank | DB14540 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.869 |

| EC Number | 208-170-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 63963 |

| KEGG | C01082 |

| MeSH | D003968 |

| PubChem CID | 3037576 |

| RTECS number | AH3675000 |

| UNII | JW5952800J |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | CuC₂H₃O₂ |

| Molar mass | 181.63 g/mol |

| Appearance | Reddish-brown solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.56 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | -2.0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 14.1 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.544 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 120.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -216.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -732.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V08CY09 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H332: Harmful if swallowed or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-3-2 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral (rat) 710 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 710 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | Not Established |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible): 1 mg/m3 (as copper dust & mist) |

| REL (Recommended) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Copper(II) acetate

Silver acetate Gold(I) acetate |