Copper Acetate: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

The story of copper acetate goes back much further than most would guess. Ancient alchemists and early chemists realized that copper paired with acids produced vibrant blue-green salts. Copper acetate emerged as a prized pigment in Byzantine and Renaissance palettes—painters called it verdigris, coaxing those blue-greens from weathered copper and sour wine. By the nineteenth century, chemical synthesis had largely replaced the old fermentation barrels, and manufacturers could stamp barrels labeled “Crystallized Blue” with confidence. Old recipes blended curiosity with risk: apothecaries kept it on hand for dyeing, medicine, and more questionable remedies. Over time, concern for purity, toxicity, and safer handling refined the art to science, shaping modern protocols and GMP standards.

Product Overview

Copper acetate finds a role in research, textiles, and specialized chemical processes. Lab suppliers and industry catalogues offer it as blue-green crystals or powders. The product often goes by monohydrate (Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O) or the anhydrous form. Manufacturers pay close attention to the raw materials and controlled environments to meet the varying purity grades. Whether destined for a classroom, a battery pilot project, or a paint plant, the compound draws on a tradition of precision, and the differences in purity and grain can matter more than the average user expects.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Recognized by its deep bluish-green tint, copper acetate stands out on any bench. The solid dissolves readily in water and ethanol, breaking into ions that drive reactivity. The hydrated form melts at about 115°C, losing its water long before decomposition. Solutions take on vivid blue, a reliable indicator in demonstration reactions. Chemically, this compound remains a standard copper(II) salt—moderately stable, but reactive enough for key transformations. Exposure to light doesn’t do much, but enough heat brings decomposition, and that familiar burnt-acetic acid smell tells a story of chemical change.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reputable suppliers provide details like assay percentages, trace metal content, density, solubility, and particle size. The labeling includes safety pictograms according to GHS, storage recommendations, and detailed hazard phrases. Typical copper acetate monohydrate arrives at 98%+ purity, low levels of iron or other metals, and batch-specific COAs. Customers scrutinize these sheets—not just for compliance, but for assurance that trace impurities won’t sabotage a synthesis or skew research data. Each drum or bottle reflects packed accountability, reinforced by regulatory oversight and documentation trails.

Preparation Method

Most copper acetate comes from reacting copper(II) oxide, copper(II) carbonate, or metallic copper with acetic acid. Large reactors or glass-lined vessels guarantee the cleanest results. For the monohydrate, distilled water and glacial acetic acid help control any side reactions. Sometimes companies use recirculation or filtration to pull away insoluble particles. In the last step, slow evaporation creates striking blue-green crystals, which get dried and sieved to customer specifications. Small-scale syntheses in academic labs still echo the bigger process—responsible ventilation, measured additions, and careful handling all play a role.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Copper acetate’s reactivity opens doors for organic and inorganic transformations. From classroom double-displacement reactions to syntheses of copper-based catalysts, the salt delivers consistency. In organometallic chemistry, it mediates oxidative coupling or forms complex structures around organic ligands. Artists and conservators sometimes use its chemical action for patination, changing copper to brilliant greens on sculpture. Researchers have shown it can facilitate redox reactions, offering a copper(II) source for electron transfer steps. Modifications—like ligand substitution or coordination with dithiols—create an array of copper complexes tailored for sensors, electronics, or antimicrobial surfaces.

Synonyms & Product Names

Over centuries, copper acetate gathered a list of names. Verdigris, cupric acetate, copper diacetate, and “blue verdigris” all refer to the same basic chemical. Paint-makers and old texts named it Spanish green, shifting the label for specific grades or crystal forms. IUPAC designates it as copper(II) acetate, highlighting the +2 oxidation state. Technical suppliers often mark it by formula—Cu(OAc)2 or Cu(CH3COO)2. In catalogs, both monohydrate and anhydrous forms crop up, with clear CAS numbers for regulatory consistency and purchasing accuracy.

Safety & Operational Standards

Nobody approaches copper acetate casually, at least in a professional setting. It takes gloves, eye protection, and in many cases a fume hood. Ingestion brings risk—both from copper’s toxicity and the corrosive bite of acetic acid. Dust needs to stay out of the air. Long-term handling calls for ventilation, and environmental regulations require careful waste collection to keep copper out of waterways. Knowledgeable users take care with storage: sealed containers, clearly marked, away from food or flame. Companies offer regular safety refreshers, and university protocols underline that “historic” materials like verdigris demand twenty-first-century respect.

Application Area

Copper acetate enjoys surprising range. Textile dyers once used it to produce goat’s hair and silk in vibrant blue-greens. Today, agriculture leans on copper-based chemicals for crop protection, though concern over copper’s environmental persistence prompts tighter controls. Laboratories rely on it for analytical chemistry, as a catalyst, and even in battery research for its redox properties. Art supply distributors still list it, especially for patina solutions. Electronics labs explore its use in new semiconductor and conductive polymer applications. In the classroom, instructors demonstrate classic precipitation reactions, teaching a new generation basic stoichiometry and colorimetric analysis.

Research & Development

Scientists keep pushing the boundaries of copper acetate chemistry. In the lab, it supports novel material synthesis, especially as green chemistry focuses on environmentally friendly catalysts. Battery developers examine it as a candidate for electrode coatings, looking for stable, high-capacity materials. In medicine, antimicrobial coatings based on copper complexes draw attention for use in hospitals and high-touch surfaces. Researchers probe its interactions with biopolymers, hoping to design smarter drug delivery vehicles or imaging agents. Fundamental studies dig deeper into its coordination chemistry, building a better understanding of copper’s flexible electron behavior.

Toxicity Research

Copper acetate doesn’t leave health conversations easily. Chronic exposure brings risk: too much copper disrupts enzymes, harming liver and kidney function. Inhaled dust or accidental ingestion create headaches, nausea, and metal taste. Regulatory agencies like OSHA and the EPA set exposure limits and track environmental levels. Recent studies investigate sub-lethal effects, especially for agricultural runoff and aquatic toxicity. Schools and hobbyists face educational campaigns about safe storage and disposal. Companies work to reformulate or replace copper acetate where safer alternatives exist, balancing performance with responsibility. Researchers explore bioaccumulation, signaling that future regulation may only tighten.

Future Prospects

Copper acetate’s story continues, shaped by science and society. Renewed research in sustainable chemistry may drive demand for more “green” copper catalysts, especially as pressure mounts to find alternatives to precious metals. In energy, next-generation batteries and fuel cells present opportunities—especially if copper-based materials lower cost and improve recyclability. On the regulatory side, growing awareness of environmental and health risks sparks calls for safer formulations, more robust waste treatment, and better risk communication. Academic collaboration with industry might uncover niche uses in nanotechnology, art restoration, or even medical diagnostics. For all its long history, copper acetate remains a chemical that invites both caution and curiosity, promising value where knowledge and safety walk hand in hand.

Why Copper Acetate Matters in Daily Life

Most people don’t think much about the chemicals that help modern life move forward, but copper acetate walks silently through lots of industries, from farming to painting. This blue-green compound, usually arriving as flakes or crystals, brings more to the table than just an eye-catching color. It’s easy to dismiss something with a name that sounds like a science class relic, but copper acetate has a job list that stretches farther than you might expect.

Helping Crops Stay Healthy

In agriculture, diseases spread by fungi can wipe out crops in bad years. Copper acetate, when mixed into certain fungicides, gives plants a fighting chance. Farmers use it to hold back blights, mildew, and leaf spots, especially on fruits and vegetables. Folks who’ve had a summer tomato patch may not realize a sprinkle of copper acetate out in an orchard’s spray tank helps keep the fruit they see in stores looking good. The compound breaks down in the environment faster than some older pest-killers, so it helps strike a balance between farming and environmental concerns. According to research from the Food and Agriculture Organization, copper-based products remain vital for plant protection in organic and conventional farms alike.

Making Colors Pop in Art and Industry

Walk through an art supply shop and you’ll often find copper acetate has had a hand in pigment production. In the past, artists treasured its role in producing verdigris, that distinct green used in Renaissance paintings. Today, artists and makers still seek copper acetate for specialty colors in ceramics and glasswork. In textile dyeing, this salt helps set color and produce shades that stand out—without it, many blue and green fabrics would look dull. In my own studio experiments, trying to tint pottery glazes, I noticed a splash of copper acetate gives a subtle shimmer and richness that cheap substitutes can’t achieve.

Tiny Reactions That Power Big Industries

Copper acetate wears another hat in chemical reactions. Scientists in laboratories rely on it to speed up specific reactions or create unique molecules in the process of making medicines or new materials. In chemical manufacturing, this compound acts as a catalyst, pushing forward reactions that might otherwise crawl at a snail’s pace. Here, efficiency matters—a poorly-run reaction means wasted energy and materials. Chemical plants that use copper acetate often save both money and time.

Sensitive Uses in Science and Safety

Research labs turn to copper acetate as a reference in experiments where measuring copper levels accurately makes or breaks results. Water quality testing sometimes involves copper acetate standards to compare readings, making sure what comes out of a tap stays safe to drink. In smaller quantities, copper acetate plays a role in producing organometallic compounds, which become building blocks for everyday items such as plastics, coatings, and electronics.

Risks and Responsible Use

Handling copper acetate needs care. Direct contact can irritate skin and breathing it in can bother lungs. Proper storage, protective gear, and training in its handling cut down on risks at farms, factories, and schools. Groups like the World Health Organization and national environmental agencies keep watch over copper levels in soils and water, setting limits so use doesn’t stack up and harm wildlife or people.

Searching for Safe Solutions

Alternatives matter as well. Designers of crop protection products, artists, and chemical engineers constantly test new formulas to reduce copper use without giving up on performance. Many research groups focus on delivering plant treatments right where needed or switching out copper for less persistent compounds. In the end, finding that balance means listening to science, keeping safety in mind, and remembering that even the most ordinary-sounding substances touch our lives in unexpected ways.

Digging Into What Makes Copper Acetate a Concern

Copper acetate shows up in labs, art studios, and sometimes in chemical experiments at school. The stuff looks harmless—green-blue crystals, easy to mistake for some quirky craft supply. That kind of thinking can lead folks to overlook the risks that come with handling it. Years back, I worked with metal patinas, and a friend used copper acetate in a home art project. She wore gloves and goggles, but I still remember the sharp warning on the label: “Harmful if swallowed. Causes skin irritation.” The stuff definitely deserves respect.

How Copper and Acetate Compounds Affect the Body

Copper plays an important role in the body, supporting functions like building red blood cells and keeping nerves healthy. Eating too much copper—by accident, often through contaminated food or water—triggers problems most people would rather avoid. Copper acetate doesn’t belong in anyone’s food or drink. Swallowing even small amounts can upset the stomach, bring on nausea, or send you racing to the restroom. Higher doses have caused liver and kidney issues in documented poisonings. You might not expect it, but these symptoms can creep up after repeated small exposures in the air at some old factories or workshops.

Handling Risks in Schools and Workplaces

In school labs, teachers know to keep copper acetate in clearly labeled bottles and lock up the stockroom. A single whiff of its acetic acid smell sometimes gives away a spill—even if you can’t see the crystals, you know something’s off. OSHA, the EPA, and Health Canada have their own rules for safety. Touching the powder with bare hands leads to skin and eye irritation, and breathing in dust causes sore throats or coughing. In my own work, washing up after use and never mixing it with bare skin meant far fewer headaches. Gloves and goggles sit at the top of any safety checklist when it appears on the materials list.

Environmental Concerns and Copper Runoff

Most people focus on safety data sheets for personal health, but copper acetate threatens fish and insects too. Even small spills around streams or school drains get picked up by local water testing. Too much copper blocks plant growth and can kill fish. Farms using copper compounds sometimes struggle to keep runoff measured, and environmental groups keep close tabs on copper levels in rivers. Cleanup procedures after use become just as important as storage, and leaving waste to wash down the drain creates bigger problems downstream.

Reducing Hazards With Smarter Choices

Chemistry classes and art projects don’t need to stop just because a substance poses risks. Having clear labels on all bottles, keeping a spill kit close, and setting up rules around storage take just a little planning. Phone numbers for poison control stations belong on the lab wall. If a project allows a safer substitute with less risk, I usually take that road. For jobs where you actually need copper acetate, following directions, washing hands, and using the right gear makes a world of difference. Sharing clear facts about what these chemicals do in the body helps others avoid easy mistakes.

Final Thoughts on Respecting Chemical Hazards

Copper acetate stands out as a chemical that needs a steady hand. Most side effects come from skipping over safety steps or underestimating how much exposure matters. The facts show trouble comes through ingestion, skin contact, or environmental release. Practical routines—good habits in labeling, handling, and waste disposal—go a long way. Teaching respect for chemicals, based on experience and real science, shields both people and the environment from needless harm.

Unpacking the Hazards

Copper acetate looks harmless—its bright blue crystals could almost pass for an art supply. Yet, this compound packs a punch if handled the wrong way. Many people underestimate risks when dealing with salts like this. These risks catch up fast: copper acetate irritates the skin and eyes, and if inhaled or ingested, it triggers serious reactions. From my early days supervising a college chemistry stockroom, I learned that clear rules and a bit of common sense save people from nasty accidents.

Why Storage Matters

Humidity, heat, and cross-contamination turn copper acetate into a problem. Once, our lab saw green spots forming across a shelf from a leaky bottle. Turns out, excess moisture had seeped in and caused the acetate to react, corroding the metal shelf beneath. That’s not just a mess—improper storage means altered compounds, unreliable lab results, and expensive cleanups. Moisture isn’t the only enemy. Airborne dust from other chemicals, sunlight, and even the wrong shelf-mates can affect this chemical’s stability. Mixing up bottles during spring cleaning led to a minor fire once: copper acetate reacts sharply with strong acids and oxidizers.

Safe Storage Plan

Secure storage starts with a tightly sealed container. Polyethylene or glass bottles with screw caps seal out air and dampness better than makeshift lids or paper stoppers. Labels need to stand out—large, bold writing showing both the compound’s name and its hazards. It surprised me how many containers my colleagues left with faded labels or hurried initials. A simple relabel with chemical-resistant tape goes far to avoid mistakes.

Next, temperature control works wonders. Copper acetate stays stable in a cool, dry spot. Direct sunlight or shelf space near heating vents invites problems, as heat speeds up degradation and spills. I once stacked copper acetate with a box of sodium hypochlorite. Without thinking, I wedged the box against a radiator. Temperature swings led to sweating bottles—luckily, we caught it before corrosion or a leak developed.

Segregating chemicals makes cleanup easier and accidents rarer. I always set copper acetate in its own section, away from acids, peroxides, and flammable materials. Color-coded shelf liners actually helped—blue tape for metals, red for acids—creating a visual map for busy hands. Maintaining a dry silica gel pack in the storage bin tacks on extra protection against moisture. Regularly checking for leaks, crystals around lids, or corroded caps prevents bigger problems down the road.

Waste and Emergency Steps

Disposing of old or spilled copper acetate never calls for wishful thinking. Municipal drains and general trash bins stay off-limits. Containers must head to a certified hazardous waste handler who can recycle or neutralize copper safely. During spills, gloves, goggles, and a dust mask do more than just follow safety posters: they keep you out of the emergency room. Spilled crystals sweep up easily, but spray the area with water and a bit of sodium carbonate to neutralize residues.

Policies and checklists may sound tedious, but real-world experience argues for routine: log every opening, every container, every disposal. Everyone remembers refrigerator “science experiments”—leftover lunch oozing from a hidden Tupperware. Copper acetate deserves more respect. Safety rules, routine maintenance, and clear communication keep labs operating and people healthy.

Looking Inside the Green-Blue Crystals

Copper acetate always stood out to me during high school chemistry labs. Its bold color could wake up a tired classroom and it was usually the one compound even non-science folks recognized by sight. The chemical formula, Cu(CH3COO)2, looks simple on paper, but there’s a kind of weight to those letters and numbers that speaks to copper’s real history in chemistry. This compound serves as a direct line to copper’s story—visual, practical, and woven into industry, research, and even art. Even Vermeer used copper acetate as a pigment in his unmistakable greens and turquoises.

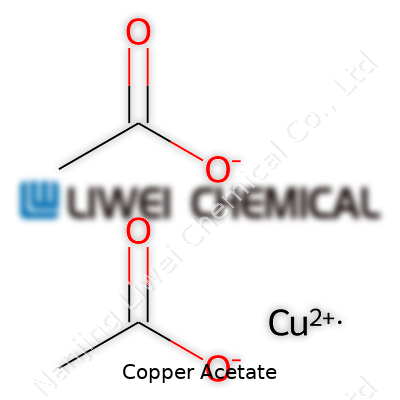

Breaking Down the Formula

Chemistry textbooks or a quick search online often just hand you the answer: copper acetate comes out as Cu(CH3COO)2. Some teachers rhyme it off as “copper two acetate” or “cupric acetate” for old-school terminology. The structure tells a straightforward story: copper in its +2 state (Cu2+) paired with two acetate ions (CH3COO-). The acetate bit comes from acetic acid, the source of vinegar’s tang. Chemically, it's the meeting place of an everyday metal and a ubiquitous organic acid, forming a compound used around the world in labs and factories.

Why the Formula Actually Matters

I have watched students treat formulas as trivia, but knowing what Cu(CH3COO)2 represents makes a big difference in real-life experiment safety and product development. The hydrated version—copper(II) acetate monohydrate, with an extra water molecule—often finds its way into chemistry sets. Its formula bulks up to Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O. This matters in industry, affecting everything from pigment quality to pesticide formulation.

Copper acetate’s place in the world goes beyond just coloring solutions. Textile producers add it to dye recipes; organic chemists grab it for its catalytic powers, speeding up tough reactions. Writing the formula out correctly means you avoid expensive or even dangerous mix-ups. Think about the classroom: a single missed hydrogen or oxygen sometimes leads to a reaction gone wrong. In manufacturing, sloppy measurements can waste batches of raw material and cost real people their jobs.

Tackling Misunderstandings and Improving Lab Safety

Mistaking copper acetate for a similar copper salt doesn’t only disrupt classroom experiments. Skin exposure can cause irritation. Swallowing it, even in small amounts, is a health risk. The formula isn't just academic—it keeps students and workers out of the hospital. Getting it right leads to safer, better outcomes in real labs and keeps paperwork clear for any quality checks.

Fact-Checking in a World of Fast Information

These days, with information moving at light speed, copy-and-paste research adds another layer of risk. I’ve seen company reports copy the wrong formula from unreliable websites. That’s not just embarrassing—it can violate product regulations and lead to failed shipments. Trustworthy data about copper acetate’s formula doesn’t just stroke egos. It builds trust with regulators, customers, and everyone from supply chain staff to the families who use the end products. Sticking to verified sources—textbooks, reputable chemical databases, anything with peer review—does more than avoid mistakes. It keeps the whole supply chain honest and reduces the risks all down the line.

Everyday Chemistry in the Spotlight

Copper acetate gets plenty of attention among science fans and professionals. Its bright blue-green color grabs your eye, but more than that, its behavior in water shapes how people use it. You’ve probably run across copper compounds in your garden, hardware store, or even in art supplies, maybe without realizing. That real-world link shapes how we think about this otherwise “textbook” chemical.

Solubility—Real-world Effects

Drop a bit of copper acetate in water, and you’ll see it dissolving, blending right into the liquid after a short wait. This isn’t some rare party trick to impress at dinner. This solubility is what makes copper acetate valuable for agriculture, pigment production, and classroom experiments. Farmers depend on water-soluble copper compounds to fight fungi and bacteria on tomatoes, grapes, and more. If it didn’t dissolve, those fungicides wouldn’t spread across leaves or roots, and crops would suffer. The same dissolved copper acetate finds its way into the chemistry set for school science fairs, helping students watch color changes or create metallic copper using simple reactions.

In labs, chemists measure the solubility of copper acetate at about 7.2 grams per 100 milliliters of water at room temperature. That’s a solid chunk—enough for real applications. It’s less than table salt, but enough to ensure it travels through water-based processes. Solubility rises as water gets warmer, too, so summer fieldwork benefits even more from easy mixing. This consistency means professionals can rely on copper acetate, knowing what to expect every time they prepare a solution.

Health and Safety—A Few Precautions

Copper has been used as a remedy and preservative for centuries, but not everything about it brings only benefits. Like many minerals, copper plays a role in our diets, yet too much can become risky. If dissolved copper acetate spills into drinking water, it can raise copper levels, and high doses can lead to gastrointestinal problems. That’s not just theory—municipal water systems regularly test for copper, and the Environmental Protection Agency sets strict safety limits in the U.S.

So, handling dissolved copper acetate takes some thought, not just in industry but also at home. Simple actions—wearing gloves, avoiding accidental spills, following label instructions—keep children and pets safe. Schools and agricultural workers also carry the responsibility to teach and learn safe handling. Understanding where copper ends up makes a difference. Wastewater run-off from greenhouses, for example, sometimes carries dissolved copper compounds, which can disrupt aquatic life when not properly filtered.

Solutions and Smarter Practices

Wastewater treatment plants often use filtration or chemical precipitation to pull copper ions from water before it gets released back into rivers. That takes investment and commitment—public agencies and private companies both play a part. People involved in gardening or home pest control can make small choices too, like following recommended dosages, using barriers to minimize run-off, and choosing formulations with minimized environmental impact.

Education keeps things moving in the right direction. Farmers, students, and policymakers work together to share up-to-date science, pay attention to new environmental risks, and balance benefits with responsibility. Copper acetate dissolves with ease, which opens doors but also calls for mindful stewardship.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper(II) acetate |

| Other names |

Cupric acetate

Copper(II) acetate Acetic acid, copper(2+) salt Copper diacetate Verdigris |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒpər əˈsiːteɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 142-71-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3566586 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32597 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL510660 |

| ChemSpider | 7467 |

| DrugBank | DB14597 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03d2c21d-2310-4f21-ae56-2e0e54150b2a |

| EC Number | 204-169-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 16757 |

| KEGG | C01778 |

| MeSH | D003984 |

| PubChem CID | 8149773 |

| RTECS number | GL7490000 |

| UNII | 1IYFB6XLYY |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020173 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Cu(CH₃COO)₂ |

| Molar mass | 181.63 g/mol |

| Appearance | Blue-green crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.57 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 72 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -1.27 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.2 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.27 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −32.9×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.542 |

| Dipole moment | 2.53 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 155.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -676.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -849.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CX04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation, toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H332: Harmful if swallowed or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | P234, P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat: 710 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50, Oral (rat): 710 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | AJ1925000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 1 mg/m³ (as Cu) |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.1 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 100 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Copper(I) acetate

Copper(II) chloride Copper(II) sulfate Copper carbonate Copper(II) oxide Acetic acid |