5-Hydroxymethylfurfural: A Deep Dive into A Multifaceted Compound

Historical Development of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, often abbreviated as HMF, came into focus for scientists around the turn of the 20th century, during a period when the world was hungry for alternatives to fossil fuels and traditional chemicals. Chemists noticed its formation during sugar processing, specifically through the acid-catalyzed dehydration of hexoses like glucose and fructose. Over the decades, its profile grew larger with a rise in biorefinery research, making it a signature biomolecule in the quest for renewable chemicals. The renewed attention hasn’t just been academic—industrial and governmental sectors began investigating HMF as a way to build a bridge from biomass to both fuel and advanced materials, sowing seeds for biotechnology revolutions.

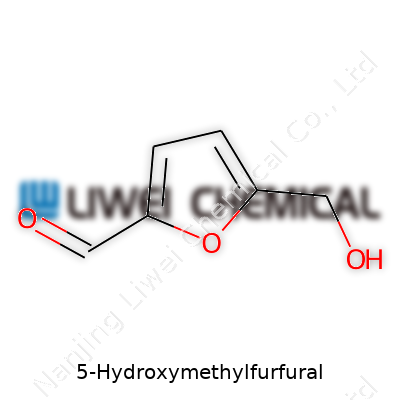

Product Overview

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural exemplifies what’s possible with plant-based chemistry. It’s an organic compound that forms the midpoint between sugars and a toolbox of downstream chemicals. HMF sits at a unique spot: not entirely a fuel, not quite a raw agricultural product. Instead, it links plant biomass to industrial and food applications. You’ll find HMF in trace amounts in many heat-processed foods—its presence isn’t just an academic curiosity; it’s a real-world indicator of both food quality and thermal processing impact.

Physical & Chemical Properties

If you were to pour out HMF in the lab, you’d see a pale yellow to brown crystalline solid, depending on purity. It carries a mild caramel-like odor—a trait that gives away its roots in sugar chemistry. Boiling occurs around 114-116°C at reduced pressure, and it melts in a range usually between 28 to 34°C. Its molecular formula, C6H6O3, reflects its dual identity as both a furan derivative and an alcohol. The structure features a furan ring attached to an aldehyde and a hydroxyl group, creating a playground for reactivity. In water, it shows moderate solubility, while ethanol and other polar solvents dissolve it fairly well. Instability creeps in with high moisture and alkaline conditions—HMF decomposes, morphing into less desirable byproducts.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

In industry, technical standards demand precise characterization of HMF. Most commercially available HMF comes with minimum purity, often crossing 98%. Labels must report actual content, melting point, and accepted impurity profile, especially if destined for sensitive applications—from pharmaceuticals to food additives. Safety datasheets, batch numbers, storage conditions, and hazard symbols always accompany each container, reflecting strict regulatory oversight. Such granularity in specification reflects only part of why HMF remains trusted in critical R&D pipelines—users can’t gamble with unknown contaminants, especially when scaling up for pilot or production runs.

Preparation Method

Scientists and industry both prepare HMF mainly by dehydrating hexose sugars. Fructose tends to dominate as a feedstock because it’s more reactive, and acid catalysts (both mineral acids like sulfuric acid and solid catalysts) drive the dehydration. You’ll see both batch and continuous processes in labs and demonstration plants, with temperatures typically hovering between 120°C and 200°C to balance yield and selectivity. Feedstock choice, pH, solvent, and reaction time all impact not only how much HMF turns out but also how much mess—side-products like levulinic acid and formic acid plague inefficient conditions. Innovations try to sidestep these issues, including biphasic solvents, ionic liquids, and catalytic systems that lower energy use and bump up selectivity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemically, HMF acts as both a platform and a toolbox for synthetic chemists. The furan ring, hydroxyl, and aldehyde groups all beg for conversion. Oxidize HMF and you get 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), an important monomer for making bioplastics such as polyethylene furanoate (PEF)—a true competitor to oil-based PET. Hydrogenating HMF’s aldehyde yields 2,5-bishydroxymethylfuran, opening doors to specialty polyesters or polyurethanes. Even reduction of the furan can lead toward levulinic acid derivatives, pushing HMF’s utility beyond just being an isolated intermediate. Each downstream chemistry unlocks new industrial and ecological value.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists will recognize HMF under several aliases. The most common, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde, comes up throughout synthetic literature. Sometimes it surfaces labeled as 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural, or simply hydroxymethylfurfural, especially in food science. Older texts might refer to it as 5-hydroxymethylfurfuraldehyde. For trade and research, you’ll see names like “5-HMF” or “Furan-2-carbaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-.” Whatever the name, its molecular signature remains easy to spot.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safe handling of HMF sets strict boundaries, given its phytochemical identity and reactivity. Though not overly volatile, dust inhalation and direct contact need engineering controls—good lab ventilation and PPE keep exposure manageable. HMF can cause skin and eye irritation, and prolonged inhalation might stress respiratory pathways. Globally, agencies like OSHA and ECHA expect chemical producers and users to train staff, restrict release into the water cycle, and adopt spill response protocols. Fire safety comes into play, too, since HMF (like many organic compounds) burns with a fierce intensity under the right conditions. Clearly labeled containers, spill kits, and regular SDS review form the backbone of safe operations.

Application Area

HMF finds itself in a diverse set of roles, which speaks to how far green chemistry has come in reshaping industry norms. Major destinies for HMF include acting as a feedstock for the production of bioplastics such as FDCA, a move that shrinks dependence on oil and reduces the carbon footprint of consumer packaging. Pharmaceuticals also tap into its furan scaffold, using modified HMFs as building blocks for novel drugs. In food science, HMF appears as both a process marker and, less ideally, as a potential contaminant—roasted coffee, honey, and baked goods all carry varying traces, and regulators watch these levels to safeguard consumer health. Outside these primary sectors, HMF’s use as a precursor for specialty solvents, resins, and advanced polymers continues to grow alongside sustainable material R&D.

Research & Development

The push for better HMF processes mirrors the world’s larger goals for cleaner, more circular economies. R&D teams experiment continuously to raise yields, cut down waste, and use non-toxic, renewable catalysts. Universities and research institutes compete and collaborate to crack the code on using lignocellulosic biomass—turning agricultural wastes straight into HMF, making every corn husk or wheat stalk a chemical factory. Computational chemists model reaction paths, searching for the lowest-energy routes and new catalyst designs. Plenty of the action sits at the interface of chemical engineering, environmental science, and industrial design, hoping to scale smart lab results into profitable, safe, and scalable industrial flowsheets.

Toxicity Research

Studies on HMF toxicity started surfacing notably in the last few decades, once routine food analysis revealed its presence in everyday diets. Rodent models gave clues that, in high doses, HMF can induce liver and kidney stress, and its breakdown products—especially in weakly alkaline environments—occasionally appear genotoxic. Real exposure levels for the average person tend to stay well below danger zones, but regulatory bodies remain vigilant. Stakeholders in food safety and occupational health watch new data closely, pushing producers to keep exposure below prevailing safety thresholds. As research gets deeper, scientists hope to clarify mechanisms by which HMF and its byproducts interact with human biology, laying the groundwork for better consumer protections and workplace standards.

Future Prospects

The future of HMF isn’t locked down just yet, but early signs suggest it might rival some traditional petrochemical building blocks. The growing need for sustainable materials, high-performing bioplastics, and green solvents drives innovation from labs to factories. If emerging catalytic systems can turn agricultural and forestry residues straight into HMF cost-effectively, it could reshape supply chains, reinvigorate rural economies, and take the pressure off petroleum. Bottlenecks still exist: process stability, product separation, and valorization of byproducts need more attention. But with smart minds, strong policy, and market demand, HMF could open a path for biomass to deliver not just fuels, but value-added, eco-friendly chemicals for the global marketplace.

From Sugar to a Chemical Powerhouse

Anyone who has left honey sitting on a sunny windowsill has watched it darken. That’s no magic trick—it’s chemistry, with a molecule called 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) right in the spotlight. HMF shows up when sugars break down under heat, and science keeps finding new ways to put it to work.

Green Chemistry’s Secret Weapon

For years, the chemical industry leaned heavily on oil. Making plastics, resins, and fuels started with a barrel of crude. HMF, though, comes from plants—corn stalks, old bread, even orange peels. Factories transform these leftovers into HMF by heating or catalyzing the sugars. Because it starts with renewable stuff, HMF fits right into the vision for greener, cleaner manufacturing.

Scientists and engineers care about HMF because it fits as a “platform chemical.” That means it’s a starting point for all sorts of useful things. HMF can turn into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), which companies use to make a kind of plastic called PEF. PEF bottles and food packaging keep out oxygen better than PET, the basic plastic that fills recycling bins. PEF comes from plants, stands up better to heat, and doesn’t depend on fossil fuels. I remember holding a prototype water bottle made from PEF—it felt just like anything on the supermarket shelf.

The Food Safety Puzzle

HMF isn’t only for factories. Chemists test for it in foods and drinks. Honey, fruit juice, coffee—if it’s sweet and processed, it probably holds some HMF. High levels signal that a product spent too long at high temperatures. My grandmother always warned against “scorched” jam, and now I know why—elevated HMF can mean the fruit lost both nutrition and flavor.

Researchers debate whether eating lots of HMF makes problems for human health. Animal studies suggest a risk in big doses. Now, food safety labs use strict rules to keep HMF below limits set by regulators in the EU or US. Checking for HMF helps protect consumers and also tips off producers that their methods might need a second look.

Fuel for a New Engine

Desperate for sustainable fuels, the energy sector watches HMF closely. Companies convert it to DMF (2,5-dimethylfuran), a biofuel with higher energy content than ethanol. DMF gives engines a kick but spares the farmland that food crops demand. I once met a team in a university lab testing small engines fueled by DMF—they swore by its clean-burning touch.

Next Steps and Roadblocks

Scaling up HMF production takes patience and creativity. Making HMF in a lab is one thing; running a plant at full tilt brings headaches and cost overruns. Yield and purity matter. Side reactions clog the process, and waste adds up. Green chemistry keeps pushing improvements—new catalysts, smarter tricks to pull HMF from tough plant material.

Finding new roles for HMF will take more work—from chemists looking for safer syntheses, to food scientists watching for unexpected health impacts, and industrial players betting on plant-based plastics and fuels. Each piece in the puzzle brings us closer to chemistry that fits the world we actually live in—where the leftovers from breakfast could end up in a water bottle, or in a greener car ride.

Understanding 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, known as HMF, turns up in foods every day. Toasted bread, honey, coffee, fruit juices—all these familiar favorites carry some of this compound. HMF forms when sugars heat up, especially during baking or caramelizing. That sweet aroma from cookies cooling on the counter? There’s HMF in there, for sure.

Where Science Stands on HMF

Few people ever hear about HMF until they fall into a science rabbit hole. But safety experts and food scientists talk about it often. The question hangs in the air: is HMF harmful, or does it belong on the long list of ingredients we eat without fuss? Here, the evidence turns complex.

Studies show humans eat HMF every single day, often without knowing it. Numbers vary—coffee can carry a few milligrams per cup, and dried fruits can pack even more. Lab experiments hint at possible health risks at high doses. Animal studies connect concentrated HMF with changes in cells that hint at toxicity. But doses in these tests tower far above what people normally get from food.

Everyday Exposure and Real-World Impact

History offers perspective. Generations grew up drinking coffee, eating bread, and spreading jam on toast, all foods loaded with HMF. Cases linking this compound to illness in humans remain hard to find. Regulatory agencies including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have reviewed available evidence and still let HMF show up in people’s food. Those bodies watch new research carefully, but for now, they don’t see enough risk at typical dietary intakes to sound any alarms.

It makes sense to stay curious. Science evolves. Even now, the jury keeps gathering information: could daily HMF build up and cause a problem? Understanding exposure over a lifetime takes more evidence. Millions rely on chemical risk assessment, and scientists owe it to society to run thorough, long-term safety studies. What gets missed in a short study can loom larger decades later.

Personal Choices and Practical Solutions

So, what steps can people take if they feel uneasy about HMF? Reducing intake means dialing back foods exposed to high heat. A few choices stand out: cut down on heavily toasted bread and charred foods, enjoy fresh fruits instead of dried ones, and use gentle temperatures when cooking at home. Drinking less coffee drops exposure a notch, but for coffee lovers, balance usually matters more than fear.

Manufacturers and food scientists keep looking for new ways to keep flavors bold but chemical byproducts low. Advanced food processing, better control of heating temperatures, and honest labeling all play a role. More companies take consumer health concerns seriously and open up about what goes into everyday foods. This type of transparency matters for everyone who cares about making informed decisions.

Moving Forward with Common Sense

No one likes finding complications in their favorite foods. Still, most of us trust that a normal plate, loaded with variety, will keep any risks—including those tied to HMF—small. Moderation, a diet rich in fresh foods, and a pinch of skepticism about sensational headlines all go a long way. Science keeps searching, experts keep talking, and the rest of us will keep enjoying our morning toast—hopefully with reassurance that food safety keeps pace with changing knowledge.

Why 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Matters

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, or HMF, shows up in some of the toughest conversations around green chemistry today. With roots in the food industry as an indicator of heating or spoilage, HMF has turned into much more than just a lab oddity. Engineers and scientists spot promise in this simple molecule because it can stand in for fossil-derived chemicals. HMF works as a bridge between plant-based sugars and chemicals for bioplastics, fuels, and even medicines. A few years ago, people hardly noticed these possibilities. Now, companies and universities worldwide compete to make HMF better and cheaper, aiming for a real shot at cutting down our growing piles of plastic and carbon pollution.

The Basics of Making HMF

Most HMF production starts with sugars. Fructose takes the lead role, but glucose, sucrose, and other carbohydrates have also joined the game. The recipe sounds simple enough: Mix sugar, add heat, and let chemicals do their work. Industrial recipes usually call for acid catalysts, which help break the sugar down in a high-temperature, sometimes water-free environment. A chemical rearrangement takes the sugar molecule and peels off water, finally shaping it into HMF.

Factories rarely use pure water in this process. Instead, they might swap in organic solvents or add salts to keep HMF dissolved and avoid unwanted side reactions. For anyone who has left a sugary drink out in summer heat, the aroma of caramel tells you what starts to happen here — though at a much larger scale and with far more control than your kitchen counter. Sometimes, reactors push temperatures well over 100°C, squeezing out as much HMF as possible without spoiling the batch with unwanted byproducts like levulinic acid or formic acid.

Making HMF Cleaner and Greener

Some early HMF processes made decent yields, but at a big environmental cost. Solvents like DMSO or ionic liquids caught headlines for enabling high production rates, though many raise eyebrows over price, safety, and recycle challenges. Over the years, the heat has shifted to water-based, recyclable, and less toxic approaches. Scientists experiment with new acid catalysts, including minerals, clays, or tailor-made solid acids. Some push for a one-pot process: sugar goes in, and HMF pours out, with little waste and easy recovery.

A handful of startups already prove that these cleaner paths work outside the lab. Avantium, a company backed by a major brewer, uses patented reactors to crank out plant-based bottles by turning sugars from corn or wheat into pure HMF. Elsewhere, university labs dig into enzymes and genetically engineered microbes that chew through plant biomass in mild conditions, skipping harsh acids and solvents.

Challenges on the Road Ahead

Real-world bottlenecks keep showing up. HMF likes to form sticky resins if left in harsh conditions or high concentrations, jamming pipes or fouling catalysts. Efficient separation and purification also cost money and energy. In my own work, I’ve seen how even tiny shifts in temperature or acidity can trash an entire run, turning most of the sugar feedstock into brown tar instead of tidy HMF crystals.

To push HMF production forward, industry and research labs focus on making everything more robust and less finicky. Smarter reactor design, new catalysts that avoid clogging, and integrated processing solutions may hold the key. Once chemistry lines up with economics and environmental concerns, HMF could become a standard ingredient — one that quietly shrinks the footprint of plastics, fuels, and more, all started from a handful of sugar.

Turning Sugar Waste into Building Blocks

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, known by many in the field as HMF, steps out from under the radar whenever people look for new ways to cut their reliance on oil. HMF forms from sugars—think glucose or fructose—using heat and acids. Instead of burning crop waste or leftover syrup, chemists grab this compound and use it as a launching pad for all sorts of chemical processes.

Plastic from Plants, Not Barrels

One story that captures attention comes from the world of plastics. Everyone sees plastic everywhere, and almost all of it starts in oil fields. More companies want to quit that. Here, HMF plays a role by acting as a stepping stone to furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid (FDCA). This acid forms the backbone of a plastic called polyethylene furanoate, or PEF. You might see PEF bottles one day on store shelves—these bottles don’t come from oil. They come from plant leftovers, thanks to HMF. Researchers in Europe and Asia seem especially keen on scaling this up.

Sweetener Industry and Flavor Science

Some industries don’t just look for green alternatives—they want new flavors and whisk in new tastes. HMF pops up naturally in honey, caramel, molasses, and roasted coffee, adding depth and character. Food chemists pay close attention to the levels of HMF. Too much, and it could signal undesirable heating or spoilage, so food safety labs often test for it. But controlled use? It helps with flavor creation or mimicry in artificial syrups or caramel coloring.

Pharmaceuticals: Not Just a Sweet Story

HMF’s story doesn’t end on grocery shelves. Scientists use it as the beginning of complex pharmaceutical molecules. You start with a sugar source and get HMF, then run a few reactions, and suddenly you have a chemical scaffold. Some of these molecules serve as anti-inflammatory agents, others as building blocks for drugs still stuck in the clinical trial phase. A few studies from universities in Germany and China have shown strong interest in developing these pathways to save steps and costs.

Biofuels and Green Solvents

Stepping away from plastics and pills, HMF serves the push for greener fuels. Companies look at turning HMF into 2,5-dimethylfuran (DMF), a liquid with high energy density—close to regular gasoline. Instead of pulling energy out of fossils, these fuels can come from corn stalks or wood chips. Some research suggests using DMF as a diesel additive, which offers cleaner combustion. As more governments set ambitious emission targets, interest keeps climbing.

Real-World Challenges and What Works

My job in a research lab put me at the bench, converting sugars to HMF. Yields never reached the high numbers the textbooks promised, not with real feedstocks—dirty mixtures, not pure chemicals. Scale-up always runs into clogging, byproduct build-up, or runaway reactions. Factories need processes that use less energy, recycle acid catalysts, and avoid expensive purification steps.

Several companies work on catalysts from minerals common in dirt or seawater, dodging rare or toxic metals. These tweaks lower the cost but also keep waste streams manageable. I’ve also seen some excitement over using water as a reaction medium instead of exotic solvents, which matters when you’re pushing for green certification.

Moving from Lab Curiosity to Daily Life

HMF stands as one step in a chain. Its future depends on people turning economic pilot trials into fully running factories. Policy can help by supporting startups and demanding more sustainable packaging or green energy. In the lab and on the ground, smart choices in catalysts and feedstocks move HMF from experimental batches to thousands of tons per year. That shift lets industry rewrite stories that once started and ended at the oil well.

Understanding What’s at Stake

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, known to most lab workers as HMF, pops up quite often in research labs, chemical manufacturing, and even discussions about renewable chemistry. Anyone who has spent time around chemical stores knows even a small slip with the wrong material can lead to a mess—sometimes a dangerous one. Most folks don’t dream about safe chemical storage, but around HMF, skipping the basics opens the door to a host of problems, from product degradation to risks for staff.

Respecting the Chemistry

HMF forms as a byproduct from sugars, a detail chemists remember because its structure makes it both useful and fairly reactive. Left on a shelf under poor conditions, it breaks down or reacts with air, spoiling the integrity of the compound. My own time handling compounds like HMF taught me that air and moisture cause trouble where you least expect it. Even a slightly wet spatula can clump up a good batch. HMF, being sensitive to oxygen, deserves careful attention to air-tight storage. Skip that, and the sample turns brown faster than most would imagine.

Keeping Things Cool and Dry

From my own benchwork, the fridge is often the unsung hero in chemistry labs. HMF stays fresher for longer at lower temperatures. A cold, dry environment, away from sunlight, helps reduce unwanted reactions. Light can speed up decomposition, so keeping it in amber bottles or cartons goes a long way. Someone once left an HMF sample on an open shelf in direct light; the color shift was obvious by noon. That wasted material and set our project back days.

Avoiding Accidents and Health Worries

Looking at safety data, HMF can irritate the eyes, skin, and lungs. Anyone handling the powder or solutions should throw on goggles and gloves, not just for show, but because those small exposures add up over time. Placing the material inside a fume hood blocks vapors and keeps the workspace safer. I’ve seen colleagues rush through work without gloves, wiping their faces later out of habit. It’s rarely a big deal until one day it is.

Labeling and Inventory—The Overlooked Basics

I don’t trust my memory when deadlines close in, and neither should anyone else who works with chemicals. Accurate, clear labeling matters: the name, concentration, and date stamped in legible ink. Anyone who has had to clean a mysterious, sticky spill knows the time lost in guesswork. Regular checks on expiration dates prevent the mess of degraded stock mixing with good samples.

Tackling Spills and Waste

My first HMF spill taught me, embarrassingly, that you can’t just mop it up with a paper towel. A spill kit with absorbent materials works better—especially if a lab mate sees you do it right. Collect waste in a clearly marked container, and don’t pour leftovers down the drain. Local regulations often treat chemicals like HMF as hazardous, and the penalties for lazy disposal sit heavy both on the wallet and on your conscience.

Bringing It All Together

Looking beyond the protocols, setting up good storage and handling routines for HMF preserves valuable product, protects staff, and keeps labs running smoothly. If companies share stories and listen to those who spend days in the lab, best practices become second nature. Sticking to basics like cold, dry storage, airtight sealing, good protective equipment, and proper labeling forms a strong line of defense against accidents and waste.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde |

| Other names |

5-HMF

5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural Furan-2-carbaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- 5-Furfuryl alcohol aldehyde 5-Hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde |

| Pronunciation | /haɪˌdrɒksɪˌmɛθɪlˈfɜːrfjuːræl/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 67-47-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 359873 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:23753 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL44743 |

| ChemSpider | 7507 |

| DrugBank | DB04200 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.018.159 |

| EC Number | 2.5.1.155 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin84135 |

| KEGG | C01440 |

| MeSH | D000068285 |

| PubChem CID | 237332 |

| RTECS number | LM7875000 |

| UNII | I9RDZ6I0YH |

| UN number | 2810 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5020185 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H6O3 |

| Molar mass | 126.11 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow to amber liquid |

| Odor | Mild, sweet, caramel-like |

| Density | 1.243 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -0.1 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.000173 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.55 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.87 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -76.2 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.517 |

| Viscosity | 29.8 mPa·s (at 25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.75 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 247.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -320.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −176.6 kcal·mol⁻¹ |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. Suspected of causing genetic defects. May cause cancer. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | 113°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 285°C |

| Explosive limits | Lower explosive limit: 2.5% ; Upper explosive limit: 19.2% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 3100 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50: 310 mg/kg (mouse, intraperitoneal) |

| NIOSH | NIOSH: OA9625000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.5 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

2-Furaldehyde

2-Furylmethanol Furfurylamine 5-Methylfurfural |